Re / Branding Melayu: fruit salad with piquant nationalism?

First published in documenta12 magazine project, for the invited Malaysian publication SentAP!, 2007

In The Matrix Laurence Fishbourne cynically welcomed us “to the desert of the real world”, a place of banal homogeneity and evolutionary fallout from that tired old buzz word, globalisation. But what if we take desert to mean ‘stripped bare’ rather than a picture of global sameness; reduced to the raw elements, un-polluted and individual – do we also arrive at a reality?

This year’s documenta 12 incites such considerations in one of its three themes, “Bare Life (subjectification)”. As our world paces forward with neo-baroque excess we need to question what drives us, collectively and individually? Who are we after the prescriptive desires and sensitivity veils are removed? And how is subjectification valued in Malaysia’s ‘real world’?

If we take the definition of subjectification from the Oxford Dictionary,

‘belonging to the thinking or perceiving subject; giving prominence to, or depending on, personal idiosyncrasy or individual point of view, not producing the effect of literal transcription of external realities’ (1.),

we might consider what role the ‘individual’ plays in constructing Malaysian ‘identity’ in contemporary art. In a nutshell, one is idiosyncratic and the other is politically motivated. Not a new idea, but by applying the documenta 12 proposition to the Malaysian art scene, we strip back the layered fabric of contemporary identity to re-engage the individual with acidic honesty.

Like the trademarks “Malaysia Truly Asia” and “Malaysia Boleh”, Malaysian contemporary art is peppered with ‘nationalist’ sentiment. It carries a distinctive flavour, equally marketable to internal and global audiences. I recall a conversation with the artist Yee I-Lann discussing the idea that Malaysia, metaphorically, was a bowl of fruit salad with very separate and distinctive flavours that together were “Malaysia Truly Asia”, but blend them and you get ‘mush’. Call it diversity … question it as propaganda … the flavour of ‘Malaysian nationalism’ in contemporary art making is safe, self-constructed and internationally identifiable.

It is obvious to anyone taking a look at Malaysia there are systems of racial advantage that flow from a nationalist stance. Perhaps this is Malaysia’s ‘desert of the real world’? I don’t have the authority to comment on such constructs as an outsider, (and coming from a place with little demonstrative nationalism, Australia, how can I begin to understand), but I can provoke thought – a position perhaps not afforded by Malaysians due to constructs such as the I.S.A. (Internal Security Act, 1960), religious sensitivity and commercial barometers. It is a thorny journey that deposits us back at documenta 12’s theme: Can we ever reach the point of ‘bare life (subjectification)’ and how does that essence of who we are translate across borders?

Strippers … the naked truth.

Since Merdeka (independence) in 1957, and later inclusion of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore in 1963 as the newly formed ‘Malaysia’, the primary focus has been constructing a post-colonial identity. Yee I-Lann is an interesting artist in this context. Her photographs digitally suture historic archival material with images that talk about place, and in doing so, illustrate a contemporary truth.

We see it unmistakably in her “Malaysiana” series (2002). These montage portraits are constructed from original negatives salvaged from the Melaka-based Pakard Photo Studio, established by Chinese immigrants in 1959. As a quasi-ethnographer, I-Lann takes these ‘authentic’ histories, dressed in aspirational post-Merdeka euphoria, and weaves them into a semiotic patchwork that visually defines Malaysian identity. Through editing and repetition, nostalgia is heightened and memory becomes a mechanism for evaluation.

Yee I-Lann, detail from Malaysiana series 2002; image courtesy the artist and Valentine Willie Fine Art

She poses the question: How have we changed with time? Has identity been increasingly politicised? Collated and viewed on mass, these portraits are no longer about individuals. We are left with their costume. Like a uniform they are a self-affirmation of identity, and at a more extreme level, racial branding. I-Lann illustrates that her bowl of fruit salad has become more neatly sliced with time.

An interesting comparison to I-Lann’s “Malaysiana” work is the portraits of Filipino photographer Poklong Anading. His “Anonymity” series (2005) similarly subjectify the ordinariness of the portrait. In the traditional convention his subjects stand directly confronting the camera, framed by the background. The subjects hold a mirror in front of their face catching the blinding reflection of the sun, obliterating any sense of identity in an over-illuminated whiteness, branded anonymous.

Poklong Anading “Anonymity #5” (2005), lightbox/ duratrans, 20.32 x 25.4 cm; Image courtesy Ateneo Art Gallery and the artist

There is a strange parallel to the sacred light of religious halos, perhaps pointing to the inseparability of Catholicism with Filipino identity, fraught with its own problems. We are left to read Anading’s sitters as a collective composition of the objects that surround the individual and, like I-Lann’s montage portrait, they beg to be decoded. So begins the game of translation.

Simryn Gills’ photographs, “A small town at the turn of the century” (2001), are a picture of where she grew up in Malaysia. Like Anading, Gill has negated any traditional engagement with her sitters by masking their identity with a ‘headdress’ made from fruit: jackfruit, rambutans, mangosteens. One can’t help but recall I-Lann’s fruit salad of separation. Fastidiously ethnographic and theatrical, Gill invites the scrutinizing of props to bring ‘the character’ into focus.

Simryn Gill “A small town at the turn of the century” (2001), C-print, 91 cm square; Image courtesy the artist

One might ponder the semantics of the headdress and why such a traditional non-Malaysian reference at ‘the turn of the century’? What does this cornucopia say of contemporary Malaysia? Gill plays with the same device of imposing translation that I-Lann and Anading do, forcing the images to be deciphered by using western pictorial conventions.

Intersections and translations

Traditionally, codes are systems that take the form of numbers, words or symbols. We can also translate objects as carrying code, or spirit. Stripped bare, the most elementary object can eloquently embody the ethos of a community; its identity, memory and history. Gill did it succinctly with her piece “Roadkill” (2000), ‘a myriad of small, crushed items of roadside litter, mounted on wheels … ready to re-enter the fray.’ (2.) Both toy-like and threatening, scattered across the gallery space this detritus embodies that ‘steam-roller’ pace of urban life – the identity of a modern city and picture of Modern Malaysia. It has been stripped back to its raw essence; our lives, metaphorically, crushed trash.

Falling within that lineage of artists who have used the found object as a kind of cultural umbilical cord and means to parry assimilation to a ‘new’ culture, Gill’s “Roadkill” has the clarity similarly witnessed in the installations of Filipino artists Alfredo & Isabel Aquilizan. They intuitively isolate an object that immediately evokes emotion and association, and like a code, allows it to run through their work accruing understanding.

Discarded rubber-slippers carrying the imprint of an individual; blankets carrying dreams; the smell of the Filipino sampaguita flower (used for daily offerings) floating in the gallery space as a subconscious unguent, or a used toothbrush, intimately personal and pragmatically disposable. The codified object becomes the collateral of contemporary art making and these artists astutely position themselves as translators or ‘intermediaries’ between the fabric of that ‘real world’ (as Fishbourne called it) and the language of international art.

Alfredo & Isabel Aquilizan “Daing” (2003), Inaugural International Eco Arts Festival, Daet, Camarines Norte, Philippines, slippers, bamboo, wind generated sound; Image Gina Fairley, courtesy the artists

Yee I-Lann finds this ethos in the landscape. Her series’ “Horizon” (2003) and “Sulu Stories” (2005) continue her earlier discussions of a “Malaysiana” metamorphosis of identity, but use the landscape as a coded metaphor. Hayati Mokhtar and Dain-Iskander Said’s multi-screen projection, “Near Intervisible Lines” produced for the 2006 Biennale of Sydney, uses the same intersection of landscape and memory as a framing mechanism. Both emphatically steer away from labelling their work as political, but given there is no Bahasa translation for the word landscape – as a concept it is a western tradition – these works are multi-layered from the outset.

Hayati Mokhtar and Dain-Iskander Said, location with talent, “Near Intervisible Lines” for 2006 Biennale of Sydney, Setiu, Terengganu, Malaysia, November 2005; Photograph Tara Sosrowardoyo

Hayati and Dain’s film embraces this ambiguity with an ethereal beauty; a whisper of ideas caught by the wind. It is subtle and seductive, but is it subversive? The film is a sensorial experience absorbed at the pace of walking through the landscape. This visitation is simultaneously displacing, romantic, and strangely comforting. Hayati explains, “We experience one landscape, but then there is another layered beneath it, and one that will be imposed upon it.” (3.)

The film speaks about a specific Malaysian location but it also speaks of nowhere in particular, allowing it to slip under radars and across borders, constructing a poetic metaphor for the global audience. Inviting solipsism, the landscape provides the point against which the self can be defined. It is simultaneously an Asian story and a contemporary story.

Malaysian artists that operate primarily within a global art environment, visually, and cerebrally, such as Hayati and Dain’s film and Yee I-Lann’s images, together with the work of Wong Hoy Cheong and Simryn Gill, for example, are malleable. How their work is translated changes depending upon where the work is viewed, rather than what is being viewed. It is an oxymoron that equally embraces the notion of ‘Re-packging Melayu’ and ‘Bare Life (Subjectification)’. Stepping from a tone of local nationalism on one hand to biennale sensation as the counterpoint, these works have the sophistication and relative neutrality that allow them to ‘shift’ under different curatorial agendas and international milieus. These artists are deeply cognisant of their surroundings and other’s codes.

Code breaking …

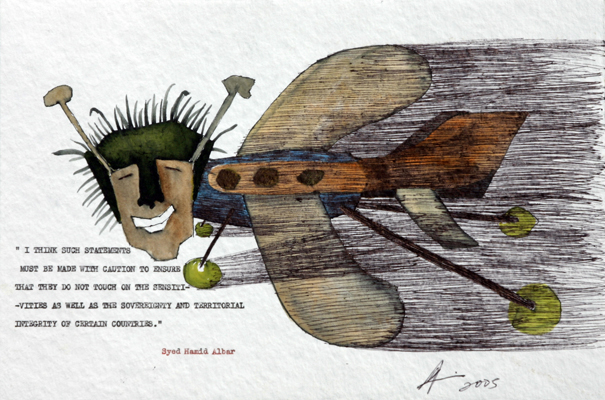

I recently became aware of a similar conundrum with Noor Azizan Rahman Paiman’s work at the 5th Asia Pacific Triennial (2006), a series of drawings called, “The Code”. These works engage our political consciousness through quotes collected and married with public figures camouflaged as monsters and anti-(heroes). They remain within the system, using text lifted from government-approved tabloids, where “the codes of history play the role as backdated reporter”. (4.) It is a cocktail of pointed jabs and satire laced with paranoia.

Noor Azizan Rahman Paiman, 2005, Private Collection; Courtesy the artist and Weiling Gallery

Speaking with Paiman in Brisbane it became apparent his work was not ‘activist’. Forever cognisant of Malaysian ‘sensitivity censorship’ and the religious-political watchdogs, he says, “The perception of political has been handcuffed by the viewer. The viewer frames me. I am Malay … for me this is a polite way.” (5.) Paiman’s drawings may be completely subjective – a psycho-moto action as he calls it – but they can’t deny that when embracing the framework and objectivity of quotation they enter the world of commentary. For an outsider viewing this work unaware of the subtleties of context, the only way to translate ‘the code’ is political. As an extreme metaphor, it is as though Paiman gives you the plane schedules, the security passes and invitation to hijack the plane and condones the action.

Wong Hoy Cheong uses the same methods in his 2006 exhibition, “Bound for Glory”. A double entendre of staged crimes, Wong chronicles Malaysian cases of rape, abduction, murder and robbery with ‘urban myth’ vigour. They are edged with the moral high ground of gossip and high art. Remove the story and what are you left with? A highly aestheticised image that sits comfortably alongside the images of Tracey Moffatt and Cindy Sherman. It is the language of film noir and the mise-en-scene of ‘biennale art’. I refer to a question posed to Wong by curator Joselina Cruz in the exhibition’s catalogue, “Do you think a piece can get so aestheticised that the history it comes from can actually get erased?’ (6.) Is this the Bare Life with which documenta 12 refers?

Wong Hoy Cheong “Chronicles of Crime” (2006), digital print on Kodak professional paper; Image courtesy Valentine Willie Fine Art, Malaysia

What is Wong Hoy Cheong’s role in constructing contemporary Malaysian myth? Does his work present a deeper, continued ‘interrogation of Malaysian socio-political history’, as local writer Carmen Nge suggests (7.), reaching back to his earliest commentaries in his landmark exhibition, “Off Migrants and Rubber Trees” at the National Art Gallery (1996)? We have to remember that the first commercial gallery opened in Kuala Lumpur in 1996, a detail that presents an interesting parallel to this discussion. Wong’s exhibition history has largely been outside Malaysia during that decade. Perhaps the greater detective story is not the re-staging of historic sensationalist crimes, but rather a game of code breaking in the staging of contemporary Malaysian art internationally.

Border + jockey:

Returning to the idea of ‘Bare Life (subjectification)’, lets look at Simryn Gill’s series “Dalam” (2001) in relation to Yee I-Lann “Sulu Stories’, exhibited in the Singapore Biennale (2006). I-Lann’s photograph “Borderline” presents a landscape divided by pylons, demarcating a briny border across the Sulu Sea as far as the eye can see. It speaks about that contentious and historically borderless territory which is not quiet Filipino or Malaysian, and is the subject of a land right claim in the International Court of The Hague. While this image investigates I-Lann’s Sabahan heritage, there is a dark undercurrent that plucks at issues pertaining to colonialism, land rights, terrorism, piracy and the exploitation of resources. These are global ideas and sit well beyond home-baked nationalism. While the tone is not political, stripped bare these works are anything but neutral.

Yee I-Lann “Borderline” (2005), from the ‘Sulu Stories’ Series, digital print on Kodak Professional Paper, 61 x 122 cm; Image courtesy of the artist and Valentine Willie Fine Art

Yee I-Lann’s images are wonderfully sensitive and lyrical, but they are also deeply layered and suggestive. There is an absence in the landscape that she uses as a ‘charge’ in both “Horizon” and “Sulu Stories”. We see it at work in “Borderline”. Gill uses a similar charged absence in her “Dalam” (2001) series, translated inside. Studiously collecting over 200 images of Malaysian living spaces, Gill blurs the genres of anthropology, documentary and contemporary photography. Her environments are coldly defining, void of any human presence. Collectively, these intimate spaces construct a picture of contemporary Malaysia and hint of individual histories, but what is being said through their absence? Does Gill present us with the rawness of a life stripped bare?

The artists discussed, Yee I-Lann, Wong Hoy Cheong, Simryn Gill and Hayati Mokhtar, speak from a position of hybrid identities; educated overseas, shown internationally, living between places. They fit within the current art world fashion of artists as border jockeys, showing up on curatorial radars for their ability to filter regional pastiche, using a visual language that is transferable. They understand the value of cultural collateral. The question is, by using the language of global art in the service of Ye Olde Nationalism, does an ersatz nationalism militate against contemporary Malaysian art developing its own voice? I am reminded of Fishburne’s synthetic ‘…desert of the real world.’

Unclogged Rojak:

Too much sauce on the Rojak (8.) and you kill the balance; not enough and gone is that distinctive local flavour. But how much sauce is enough?

An Australian band of the late 1980s, “Not Drowning, Waving”, was famous for juggling chainsaws on stage until their lead singer cut off his hand. (9.) Yee I-Lann used the same title to illustrate some of the problems we face with translation in relation to the complexity of her “Sulu Stories”. I agree with I-Lann, caution is necessary when we translate visual media … or embrace folk myth as with “Not Drowning, Waving”.

Malaysia’s contemporary art scene is a decade young. How it moves forward navigating the strict parameters of post-Mederka identity is a question for Malaysian artists to answer. I refer to the lucid comment of Lee Weng Choy, “But what does the prominence of “identity” signify, if not the fact that the production and consumption of “difference”, as well as the taste for “otherness”, have become mainstream?” (10.)

At what point does contemporary art become just capricious branding transmitted to us in a hermetically sealed form? I am no pundit to make such evaluations, but Malaysian art without its layers is like Liza Minnelli without false lashes.

Top featured image: Wong Hoy Cheong video still of Recollecting

Notes:

- The Concise Oxford Dictionary, UK, edition 1952, pg. 1264.

- John Barrett-Lennard, “Here and Now”, catalogue essay ‘A small town at the turn of the century’, published by Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2001.

- Hayati Mokhtar, interview with writer on film location, Setiu, Malaysia, 2005

- – 5. Noor Azizan Rahman Paiman, interview with writer, Brisbane, December 2006

- Joselina Cruz, “The Third Degree: Wong Hoy Cheong on Crime, Glory, Fun and Middle-Class Malaise”, catalogue essay ‘Bound for Glory’, published by Valentine Willie Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, 2006

- Carmen Nge, “Darkness Rising”, catalogue essay ‘Bound for Glory’, published by Valentine Willie Fine Art, Kuala Lumpur, 2006

- Rojak is a firm savory salad doused in a dark peanut-sauce dressing that contains shrimp paste.

- Music folk-lore provided by Tony Twigg and Wikipedia.com

- Lee Weng Choy, “A tase for worms and roses”, published in AsianVibe exhibition catalogue, Castelló: Espai D’art Contemporani De Castelló, 2002