Is Instagram art?

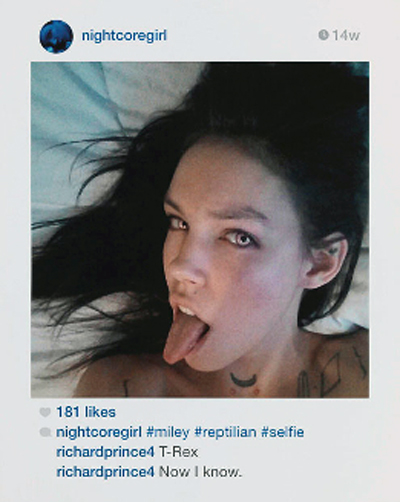

A picture is worth a thousand words; an algorithm is worth a billion pictures – how is Instagram altering creativity? Audience poses and posts with Richard Prince’s appropriated nightcoregirl from his Instagram series at Gagosian Gallery in New York.

When Mark Zucherberg announced that Facebook (FB) had acquired the startup Instagram in April 2012 in a staggering billion-dollar acquisition – just four years after the App was launched – the tech and art worlds were abuzz.

While that decision threw renewed attention on Instagram, with dialogue circulating that questioned what it was that FB was actually buying and what its perceived value was as a kind of zeitgeist of our time – was it merely an investment in its 30-million users or an investment in an art landscape?

Another conversation also started to surface. Some key players within the visual art world were using Instagram as if almost endorsing it as a creative visual medium. Renowned American photographer Richard Prince had captured the art world’s attention recycling Instagram screenshots as his own art. In September last year, the New York powerhouse gallery, Gagosian, presented a solo exhibition of his Instagram grabs, while during fair time in Miami this December, famed American art critic Jerry Saltz was stirring things up appropriating pictures of artworks with ribald comments about top drawer players, such as Zwirner and Gagosian, posted on his Twitter and Instagram accounts – all without leaving his New York office.

Additionally, Art Basel Miami corralled luminaries from the art word – Klaus Biesenbach, Director of MoMA PS1 and Chief Curator at Large at Museum of Modern Art, New York; Simon de Pury, Auctioneer, Art Dealer, New York/London; Hans Ulrich Obrist, Co-Director, Serpentine Gallery, London and “Instagram artist” Amalia Ulman – who sat down with CEO and co-founder of Instagram, Kevin Systrom, to nut out the topic: Instagram as an Artistic Medium.

So is Instagram indeed art?

Installation view of Richard Prince’s Instagram inspired exhibition at Gagosian New York; Photo Gina Fairley

What is Instagram?

We’ve all heard of it; but those of you who have not signed up to the App, here’s the scoop. Simply, Instagram is an online mobile photo-sharing and social networking program that allows an individual to crop and manipulate a digital image captured on their smart device and then post it with a comment.

Unlike Flickr, FB or Pinterest – which are vehicles for uploading your life – Instagram involves choices.

Distinctive is its square format (not unlike the old Polaroid image) and the use of “filters” that allow the user to be “creative”. Video can also be posted with a maximum length of 15 seconds. Armed with a library of twenty choices that vary exposure-contract-rotation-antiquing-colouring, essentially users have the ability to adjust “reality”. Many argue that is what photography has always done. So why the hype?

Systrom announced in Miami that, as of December 2014, Instagram had 300 million users accessing the site per month; and in 2013 it grew 23% on the heels of its acquisition. One blogger even claimed that it accomplishes what street art tried, but never quite achieved: art for the masses.

Systrom told the captivated audience: ‘What we need to do, internally, is to grab and unlock the 75+ million photos posted everyday on Instagram – people just like you – and to make connections between people who make those photos and people who want to see them…We are not a technology company we are a community company.’

Discussing the topic at Art Basel Miami, December 2014. Panel from left: Hans Ulrich Obrist, Simon de Pury, founder Kevin Systrom, Klaus Biesenbach, artist Amalia Ulman, moderator. Photo Gina Fairley

But is it art?

So is this just about the “warm and fuzzies” of sharing or is there real art content here?

Famed American photographer Richard Prince himself has spoken about the medium on his blog Birdtalk, in particular the app Tumblr that inspired him to rethink his brand of appropriation in relationship to social media: ‘The first time I saw Tumblr I saw it on my daughter’s computer. I said, “what’s that”? She had organized a bunch of photos according to color…The next question I asked her was, “whose images were those and did you have to ask “permission” to use them”. She looked at me like I was the “man from Mars”. “Permission”? “For what”? (That’s my girl).”’

In his recent Gagosian show, in the ritzy uptown gallery in New York, Prince showed thirty-eight Instagrams harvested from the Internet, which he then inkjet-printed on canvas and quickly deleted. Appropriating a Warholian formula, Prince passes off the grabs as art, which one might add have sold fabulously.

Richard Prince’s Portrait of NightCoreGirl (2014), Photo: Screenshot from richardprince4’s Instagram

Extending his position, Prince had this to say about Instagram: ‘It’s almost like it was invented for someone like myself. It’s like carrying around a gallery in your pocket.’

It is so different to John Berger’s radical tome of 1972 Ways of Seeing that attempted to democratise art – where Instagram, or other things like it (in our contemporary context), ‘should replace museums’ – to use Prince’s words.

While Prince’s recent exhibition was not discussed during the Art Basel panel (surprising given the timing), the discussion had an almost Laurel and Hardy tone as art world super trio – Biesenbach, Obrist and de Pury (the only one missing was James Franco often snapped on Instagram with each of them) – handed off on their impressions in entertaining banter. And, as curators and taste-makers globally, we tend to take notice – if not be amused.

De Pury explained: ‘Two years ago Hans Ulrich said to me, there is this amazing thing – Instagram – remember that word. It’s going to transform the world…So if Hans Ulrich told me to look at it, I immediately went and signed on, and became addicted.’

‘What I am interested in is far beyond art. I am interested in visual culture, in contemporary culture – so architecture, film, literature, theatre, art. I hate all these artificial boarders between these worlds. The great thing with Instagram is that it breaks down all these walls,’ de Pury added.

So it’s not just social media then?

Screengrab of James Franco on Han Ulrich Obrist’s Instagram

‘You have different type of artists. Hans Ulrich is the ultimate consequential artist – he is sticking to one thing, and brilliantly. His is posting stickers when no one writes any more. He is single handedly saving hand writing and in a purely visual world and he shows the power of the word, visually expressed.’

De Pury continued: ‘Klaus has his window views from New York…and he has sub groups of works within his artistic Instagram oeuvre, like his selfies.’

So there is an Instagram oeuvre – we are falling into art territory using language like that.

Screenshot from Klaus Biesenbach’s Instagram

Obrist added to the dialogue: ‘So many artists are doing main projects on Instagram’, like panelist Amalia Ulman who allowed her entire persona to be manipulated via Instagram as a performative conceptual work.

Biesenbach agreed: ‘It (Instagram) changes you and your behaviours, which is a really interesting phenomenon. I used to hate hate hate saying anything about my personal life… I really hate objects for myself (but when I got this camera) I could make pictures without being objects. I disagree with Simon. We are not artists. Not every single person on Instagram is an artist, that is compelled to make things – and that is a huge difference.’

He concluded: ‘I go back between this idea that it sits between document and fiction…It’s a very powerful tool.’

Biesenbach has become followed not only for his windows (taken from his apartment every morning), but his Chosen Family of selfies with friends and his use of the medium for activism. He recently bought the Russian group Pussy Riot to PS1 New York, only announcing the gallery’s event on the day on Instagram to a sell-out audience.

Biesenbach said that there are many pioneers, naming Yoko Ono’s publishing in the 1960s as an ‘anticipation to twitter – short sentences that knock off your shoes’. He added: ‘So many artists anticipated the theoreticality, the ficitiousness or role playing. I think now we are just co-opting them, what artists have anticipated for 40 years – it is a liberating moment.’

More and more people are “performing” their own lives. At what point does that become art?

These curators – while flirting in their realm of artists, creators – give rise to renewed questions. Indeed, Obrist has held several Instagram meets or discussion labs to explore and write the definitions of the medium. Such conversations tap into a theoretical discussion still to be had that moves from the “is it art?” question to tracing its routes within the history of artistic genres, one that speaks of a visual lineage and future.

Hans Ulrich Obrist spoke at theMillion Dollar Theatre in Downtown Los Angeles 26 July 2014, to kick off ForYourArt’s website redesign, an online source that works to advance, support, and foster a culture of dialogue by perceiving all media, sites, and relationships as potential for artistic transformation – including Instagram.

So whether Instagram turns everyone into an artist or not, the consensus drawn was that there is a difference between putting up a photo of what you are eating and using it as a medium to create. And as those 30 million uses filter, adjust, colour and post their “creative” grabs of life around them – we may not describe their output as art per se, however, we can be assured that the normalisation of a creative lens is shaping our attitudes – and that can only be a good outcome for the future.

First published on artshub.com.au, January 2015