Outside In / Inside Out: Observing contemporary Philippine art

First published in Thesis Eleven: Critical Theory and Historical Sociology, Sage Publishing UK in collaboration with La Trobe University Melbourne, 2012.

The cultural cartography: Exiting Ninoy Aquino International Airport, one is slammed with the chaotic density that is Manila: a sea of faces jostle for your attention; the air thick with heat and a haze of pollution enshrouds the scene in a halo. In recent years an ‘official’ taxi service has made the 7 km journey into Makati – the Philippines business hub and bastion of all things Western – a less anxious negotiation. Today one is transported in air-con luxury through the grid that is Manila’s perpetual traffic jam, sealed from its cacophony and urban abrasion. Vendors and street children swarm the vehicle at each pause, begging attention. And slowly you inch forward.

It is a hint at the parallel realities that define this city. From the outset Manila is an affront to our comfortable Western spatial-social sensibilities. Getting anywhere is difficult. Understanding its complexities offers an even greater challenge. Geography is an extremely layered consideration. We are not only speaking about the simple navigation of Manila’s physical landscape – be it this journey described from the airport or finding our way from one gallery to the next strung across the city – but also how we read contemporary Philippine art within a broader geographic context.

An archipelago of 7107 islands, that 20th-century dialectic of ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’ is played out in local terms as Manila-based artists and non-Manila artists. While regional centers such as the Visayas, in particular Cebu and Bacolod, Baguio in Northern Luzon, and to a lesser degree Davao in Mindanao, have their own vitality and histories as art scenes (1.), Philippine contemporary art is almost exclusively sited around ‘a Manila scene’.

It is here that careers are brokered, trends set, collectors jostle, and exhibitions rotate at a lightening pace. For this reason this article focuses on greater Metro Manila and the university belt of Quezon City for its function as a portal to international networks – both in terms of the contemporary curatorium and commercial access.

Standing on its rim looking in, Manila’s art scene is stylistically diverse, inter-generational, educated, technically sophisticated, intuitive, and bold. Given the rise of the art market in Southeast Asia, we tend to think of these as markers of our times rather than the result of a sophisticated lineage. The Philippines, unlike its neighbours, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam, for example, has a long history of the gallery-market relationship. The first commercial gallery was founded in Manila in 1950; first biennale participation was in 1953, and an award for art criticism was established in 1954. (2.) With that maturity comes a casual confidence in the way artists operate within this system, and it has permeated the work produced.

Wire Tuazon, “Landscape with Hand Grenade” (2007) oil on canvas, 72 x 48 inches; Image courtesy the artist

Fault lines are the points of fracture along tectonic plates where the geography literally shifts. If we are going to chart the geography of this art scene, we first need to step back through it to locate those flashpoints: the 1950s for its birth of the commercial gallery sector and parallel emergence of the Filipino avant-garde; the 1970s for the rise of patronage and a proliferation of museums; the 1990s for its emphasis on thematic artworks in synchronicity with the ‘biennale explosion’ and the international curator’s vision of the region; to our most recent chapter, this millennium, and the market phenomenon of ‘contemporary Asian art’ sidled with non-nation based networks, ever-expanding and driven by technology affording artists an engagement with curators, institutions and markets more on their terms than previously possible.

While this chronological narrative reads like an epiphany in bites – self-legitimizing paradigms breaking new ground – it is the residual of these events that is carried forward that I am interested. One such recurring thread is a quintessential Filipino celebration of the avant-garde position, which can be traced from the painter Victorio Edades, advocating a new modernism against ‘the conservatives’ debated in the papers of 1948 (3.), to an anti-aesthetic scene with a healthy cynicism towards systemic art structures today nurtured by Manuel Ocampo. Both artists, having been abroad, took on the zeal of the returned hero leading a new vision discontented with the local status quo.

Manuel Ocampo “Boycotter of Beauty” (2011), acrylic on canvas; Image courtesy the artist and Valentine Willie Singapore

This inflow was shared by others, parallel chapters impacting upon the styles and structure of this local landscape, illustrated by Benedicto Cabrera’s return from London post-1960s, Roberto Chabet bringing a conceptual bent, to a constant flow today of Filipino artists living abroad and bridging their practice with Manila.

Another such residual key to understanding today’s art scene is regionality. Founder of the Art Association of the Philippines Purita Kalaw-Ledesma observed that ‘in keeping with the desire to make Manila the artistic center of Southeast Asia, a Southeast Asian exhibition and competition was launched in the city’ (Ledesma and Guerrero 1974: 67). The year was 1957.

While Ledesma’s comments could describe recent activities, this fledgling engagement was unsustainably mapped in fits and starts, whereby this vision today has become de rigueur. An important idea was set in the Filipino psyche at that point: that art could transcend national boundaries and yet be intoned with a distinct national identity. It was an idea picked up more fully during the 1990s, voiced through large-scale international exhibitions such as the biennale; Australia’s version was the Asian Pacific Triennial (4.) and the Philippines became the darling of this circuit.

Rogoff describes the 1990s as concerned ‘with race and cultural difference which resulted in trying to take on the authority of “geography” as a body of knowledge with political implications’ (Rogoff 2003), and I would add a marketability within the international curatorium. While curators were observing Philippine art under one ‘cartographic sign-system’ (Maravillas 2010: 14), Filipino artists were operating under an entirely different one equally reliant on memory, access, and agenda.

Steve Tirona “Imelda Collection” (2006), Digital c-print, 61 x 86.5 cm; Image courtesy the artist

It was a decade when the alternative space reigned and, on the forward step of the People Power Revolution that toppled the Marcos regime (1986), a psyche of ground-roots empowerment permeated this art scene and the work it produced. It is this tenacity and nous that remains one of the core foundations to contemporary Philippine art today.

Tracking forward to the last ten years, locality – both literally and metaphorically – has shifted dramatically away from that 1990s landscape, from collectives and gritty alternative spaces to more sophisticated independent practice alert to the currency of international networks; from ‘the mall gallery’ (5.) to warehouse-scaled commercial spaces, and a local market that has expanded to participate in the international auction platform.

Furthermore, art fairs, greater mobility and technology have ratcheted up the visibility of contemporary Philippine art presented, and sold, abroad. What has triggered this recent change, and who is driving it, are the central questions examined here.

MM Yu “Thoughts collected, recollected” (2007), Installation view Finale Art File SM Megamall, Spiral bound photo books, dimensions variable; 2008 Ateneo Art Award Winner; Image courtesy the artist and Finale Art File

As a visitor to Manila’s art scene today you are welcomed with open arms and a sweaty San Miguel beer, pulled in with an electrifying jolt. The art feels earth-shatteringly good. Of note, several exhibitions open each night to a roving scene navigated by SMS messaging. If one does not have ‘an in’, as ‘an outsider’ this landscape is even more difficult to penetrate than the gridlock of Manila traffic.

How then, as outsiders, do we see beyond this climate of party and pace to gauge serious visual arts practice? Furthermore, when overlaid with the perceived validation of local prizes, auction results, and collecting bias, reality is an increasingly difficult navigation. Can we rely on international art magazines, art fairs, and globetrotting curators as presenting a true and reliable characterization of contemporary Philippine art? Equally, can we rely on localized memory and anecdote to relay that scene’s history, a point I will flesh out through my first case study, the artist Roberto Chabet. They are complex questions that provoke ideas of transparency, access and translation.

Understanding change

Roberto Chabet (b.1937) was appointed founding Museum Director of the Cultural Centre of the Philippines (1967–70). Designed in the classic Brutalist style of modernist architecture, it was to be ‘emblematic of the dawning of a new age in structuring culture’ (Cruz 2005: 18) and signaled to the world a culturally sophisticated Philippines under the charge of the Marcos government. However, barely a year in the post, Chabet withdrew from mounting political tensions in order to teach at the University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts, Diliman. He aligned himself with the subversive short-lived space Shop 6 (6.), citing contemporary art practice exclusively within the experimental and the non-establishment. As a teacher and curator, and with an eye consistently trained on the West, he influenced a generation of artists, many of whom define contemporary Philippine art today and yet, before the retrospective survey of his life and work, Chabet: 50 Years (2011–12) (7.), little was known of his artwork outside of Manila itself. This begs the question: Why?

Roberto Chabet, Installation view ‘to be continued’, ICAS La Salle Singapore, January

2011, ‘Cargo and Decoy’ (front) and ‘to be continued’ (rear) ‘Boat’ (left). Image courtesy the artist

and King Kong Projects. Photograph MM Yu.

This 40-year oversight ‘throws into crisis’ (Ching 2010) the reliability of Asian cultural historiographies. What we are observing is that as these ‘contemporary Asian art scenes’ are being cracked open via market interest and greater international exposure through technology, our understanding of localized visual art practice is also becoming more reflective of that scene’s diversity and own trajectory of modernism, previously skimmed over as a kind of time-lapsed appropriation. The survey’s premise was to broaden understanding of the geographic platform for conceptual art in Asia, and to redress our perception of Filipino art within international curatorial circles and the market (8.).

While I agree with Godfry and Ching’s related concerns for historic accuracy, Chabet’s survey on the contrary offers an extremely accurate indication of how this art scene works, and the clout of the artist within today’s almost frenzied climate of embracing ‘contemporary Asian art’.

Launched at Singapore’s Institute of Contemporary Arts LASALLE (ICAS), to be continued showed Chabet’s plywood constructions from 1984 to the present recreated by his past students. The exhibition was followed by Complete & Unabridged Part I (ICAS) and Part II (Osage Kwun Tong, Hong Kong), featuring 80 past students and blurring mediums and stylistic alliances within this scene. The driving point is that this unconventional survey described the inter-generational collaboration and movement across gallery sectors that epitomizes the diverse and enmeshed nature of the Philippine art world. Understanding this complexity is key to a critical appreciation of the multiplicity and nuances of contemporary Philippine art – of artists, scenes, and markets that in turn impinge in a feedback loop on the subsequent artworks created and of their receptions.

The flipside to this ‘scene-within-itself’ is whether such loyalties skew value structures and set up rubbery stylistic interpretations as ‘representational’. Chabet’s artworks asserted ideas rather than the collected object, hence little residual work remained for observers to this scene to critically evaluate his work within the context of the day, reliant on localized memory to extend that discourse. It is exacerbated by the ‘blaze and fade’ of quickly rolling exhibitions, and with no public institution in the Philippines dedicated to collecting and permanently presenting contemporary artworks as a meter of reference (9.), veracity can be questioned at home equally as its representation abroad. To recall Rogoff, ‘criticality is key to moving beyond existing frames of knowledges and allegiances’ (Rogoff 2003). The aura of the artworks take on a spectral afterglow, but their original material forms cannot be traced.

This point brings us to my second case study, the artist Manuel Ocampo. Ocampo (b.1965) lived abroad through that defining period for contemporary art practice in Southeast Asia, the ’80s and ’90s. His was an exodus shared by many artists as a kind of self-imposed political exile, including David Medalla, Gaston Damag, Lani Maestro, Lordy Rodriguez, Paul Pfeiffer, Maria Cruz, Robert Nery, and the late Pacita Abad, artists who despite location held their ‘Filipino-ness’ central to their making.

Take, for example, Canada-based Maestro’s A book thick of ocean (1983) that won the Havana Biennial Prize, a poetic lament for those who went missing during the Marcos regime; or Paris-based Ifugao artist Gaston Damag’s use of the Buloul (rice god) central to his installations, his artistic psyche inextricably linked to the northern provinces despite their conceptual delivery. While they comfortably infiltrated the milieu of international art, their work remained visually bi-lingual. It is instructive to how we view contemporary Philippine art today.

Joining this artistic diaspora, Ocampo piqued the gaze of international curators for his use of culturally provocative and blasphemous motifs, their folk-toned narrative fused with European references extremely adroit and delighting in their agitation. Ocampo’s painting Untitled (Burnt-Out Europe), censored from Documenta IX Kassel (1992), best illustrated his position. At a time of Germany’s reunification he presented a hawk-like Christ emblazoned with swastikas swooping over a concentration camp. Ocampo was, and remains, interested in how images communicate, and it sets the stage for the contemporary verbiage of his current projects and their anti-aesthetic proliferation.

Ocampo returned to Manila in 2003, and through collecting, curating, and most recently his own art space, has encouraged a stylistic shift that has ruptured entrenched value structures within Philippine painting. He thrives on dissonance and its consequences. His recent coup d’état was the exhibition Bastards of Misrepresentation: Doing Time on Filipino Time, curated for the Freies Museum Berlin, with a kernel traveling to Austria for the opening of Galerie Zimmermann KratochwilL (10.) – a group of artists he described as ‘the cutting edge of Filipino art in the last five years’ (Ocampo 2010: 8), artists such as Argie Bandoy, Robert Langenegger, Pow Martinez, Jayson Oliveria, and Jucar Raquepo.

Pow Martinez Detail “Family portrait” (2009), Oil on canvas 107 x 127 cm, 2010 Ateneo Art Award Winner; Collection Olivia Yao; Image courtesy the artist and Ateneo Art Gallery

One could posit that Ocampo rewrites historic frames of periphery and centre using his own Euro-entrée card to expose and alter preconceived readings of Filipino art abroad, adopting Frye’s adage ‘where you are is the centre’ (11.). Germany’s last substantial exhibition that repositioned Asia curatorially was Thermocline of Art, New Asian Waves (ZKM, 2007), which blatantly omitted the Philippines from this dialogue.

Was Filipino art no longer considered ‘Asian’? It is a blight countered by the biennale and auction circuits, which, catalogued by nation, celebrate the successful label of ‘contemporary Philippine artist’.

While international museum shows have held an important place in situating Filipino art since the late 1990s, of note At Home & Abroad: 20 Contemporary Filipino Artists (1998), Faith + the City (2000), Pleasure + Pain (2003), Sentimental Value: Philippine Contemporary Art Exhibition (2008), Thrice Upon a Time: A Century of Story in the Art of the Philippines (2009) and In the Eye of Modernity: Philippine Neo-Realist Masterworks (2009), Ocampo’s Bastards was less about an ethnographic frame and more about a contemporary navigation of our times. Its precursors, Metropolitan Mapping (2005), Galleon Trade (2008) and, aptly, Futuremanila (2010), provide a lineage that contests curatorial cartography by citing the Filipino abroad on his terms.

To expand, the 1990s and early 2000s was a time when governments pre-empted the passage of the avant-garde through arts funding and contrived structures of engagement. We mentioned earlier biennales, alongside these museum shows and projects such as The Australia Centre in Manila (12.), a position largely dissolved in this millennium through eroding funding and greater accountability, and a kind of reclaiming of this territory by the artists themselves. Labrador was ahead of her time when she observed:

“Artists would tap into their own networks of support, […] and engage in a form of barter trading where only goods and services are exchanged. This also applies to the art market in the Philippines … International recognition does not only mean making art that pays, but also connotes finding the means to get sponsors who can fund future work, even experimental work.” (Labrador 2005: 107)

One of the aims of Ocampo’s project was to ‘provide opportunities for the artists’ (2010: 8) and to challenge the authenticity of systemic constructs of artistic identity. For some of us this may seem like a nostalgic or romantic position and, if anything, circles us back to a question of accuracy when presented to ‘the outsider’ as the pulse of a scene now. It is a curious position for the professed ‘neo avant-garde’ bolstered by award endorsement. To help illustrate this point I turn to Ocampo’s description of his Bastards.

Five artists, Gerardo Tan, Poklong Anading, Jayson Oliveria, Lena Cobangbang and MM Yu, have been Cultural Centre of the Philippines’s 13 Artists Award recipients. Anading, Oliveria and Yu have won Ateneo Art Awards and 7 of the 14 artists have been Ateneo Art Award nominees. Gaston Damag, Maria Cruz and David Griggs have made their names abroad in Europe and Australia. Romeo Lee and Pow Martinez have been highly visible as performers in the underground art and music scene in the country. (Ocampo 2010: 8)

MM Yu, ‘Hills’ (2005) photograph, Image courtesy the artist.

He mentions two key arbiters of value: the 13 Artists Award and the Ateneo Art Award. The former, established in 1970, is awarded every three years to artists under 40 to create a new work for a joint exhibition. In contrast, the Ateneo Art Award (established 2004) is a selection by Philippine art professionals representing ‘the best’ from the past year, and in so doing defines itself as a marker of excellence spanning museums, commercial galleries and alternative spaces.

Capped at 35 years, it adopts a ‘culture of youth’ globally celebrated yet criticized for impacting collecting tastes and wider market speculation. Key to this award is that it has grown to include residencies in Bendigo (Australia), Bandung (Indonesia), Singapore, New York, and London. It is a very different climate of opportunity than the 1990s, where international exchange was driven by visiting curators and government funding bodies trying to ‘fit’ work into predetermined agendas rather than empowered local selection. It is perhaps the most important barometer of this scene today for its self-determined measure of value.

It is not surprising then that within this coterie of awardees many of the young artists actively sought, created and relished a plethora of alternative spaces and scenes that garnered vitality during the late 1990s and 2000s. A key magnet was the suburb of Cubao, which was and is attractive for its grunge urbanism and cheap rents as much as for its proximity to the university belt. This insurgent swell favored conceptually-styled installations with a Filipino make-do aesthetic – spaces such as The Junk Shop (1994–7), Third Space Art Laboratory (1997–2000), Surrounded by Water (1998–2003), Big Sky Mind (1999–2004), UFO (1999–2002), Future Prospects (2000–2), Cubicle Gallery (2002–) and Theo Gallery (2002–6), all run by artists who are today identified as the ‘established artists’ of the contemporary scene, artists such as Yason Banal, Lena Cobangbang, Geraldine Javier, Wire Tuazon, Yasmin Sison, Ringo Bunoan, Louie Cordero, Gary-Ross Pastrana, among others.

A new generation of independent spaces dissipating from that Cubao locale has reconfigured the landscape over the past five years, what Cruz calls ‘bare-faced commercial enterprises’ (2010: 50) that sit parallel to, and arguably in this slip-stream of, definitions between an established commercial gallery sector and the experimentally-minded ‘alternative’.One could argue that the modus operandi of rejection of the institutional structure and art market as ‘counter’ has become ‘alternative as extension’.

Largely located within easy distance of the Makati business belt, they have continued that experimental edge and intergenerational collaboration despite their commercial dexterity, galleries such as Mag:net galleries (2002), SLab and Silverlens (2004), Pablo (2005), Blanc (2006), MO_Space (2007), Lost (2010), and Ocampo’s Department of Avant Garde Cliches (2011). While DAGC and MO_space lean more towards a charter of international exchange programs, galleries such as Silverlens and Pablo have strategically extended their networks and visibility through participation in international art fairs.

In a similar commercial diversification, Blanc ratcheted up the activities of its warehouse residency-slash-gallery in Cubao, opening franchised venues across Metro Manila, including the exclusive Peninsular Hotel in the key international business hub of Makati, an emblematic bastion of Manila’s old-wealth establishment. Its founder, Jay Almante, described as ‘a product of the Asian Institute of Management’s Managing the Arts program’ (Cruz 2010: 50), alerts us to the increased professionalism and business focus within Manila’s visual arts sector today, despite its avant-garde foundations. This new ‘style’ of gallery describes the most discernable change to the contemporary landscape of this art scene: physically, economically, and professionally.

This recent blurring of traditional gallery tiers was evidenced by veteran alternative space Green Papaya Art Project’s inclusion in London’s TATE Modern No Soul for Sale festival of independent spaces (2010). Its founder Norberto Roldan took a ‘local event’ and made it international, then commercial – an annual exhibition that explored ‘parallel notions of seriality and counter-seriality’ (13.). Following TATE Modern, this expo-style display found its way to Singapore relabeled as the exhibition Serial Killers. The decidedly non-commercial works of Ringo Bunoan, Maria Taniguchi, and Bea Camacho, for example, while holding their integrity intact, shifted in their inflection when in the hands of a dealer, their provenance ‘value-adding’.

Chabet’s inclusion in Serial Killers with a neon-entitled PLAN B underlines this point. As the dissonant plan it reiterates the counter position, and yet its inclusion and setting in metropolitan European art markets speak more about supplying the demands of this millennium’s taste for contemporary ‘Asian’ art than about the cultural wellsprings of the art itself. It offers an erudite insight to this art scene today and its malleability to ‘fit’ the opportunity, rather than the pretense of the past where the work was selected to ‘fit’ preconceived themes set by outside curators.

Maximizing marketing, Serial Killers was timed alongside the government PR-umbrella Philippine Art Trek V (14.). However, it more accurately showcased the commercial relationship of these individual artists with TAKSU Gallery, a focus developed since 2005. Of the 40 artists TAKSU represents today, 35.7 per cent are contemporary Philippine artists, an extremely deliberate shift in its stable to accommodate market trends and offer a strong mix, from the abstractions of Argie Bandoy, Lindslee and MM Yu, photoreal paintings of Orlan Ventura and introspective portraits of Lynyrd Paras, to Roldan’s pop-animist assemblages.

Norberto Roldan, Detail of mixed media assemblage from “Everything is Sacred” (2010) at MO_space; Image courtesy the artist and MO_space

This is echoed by the activities of Artesan Gallery, Utterly Art, Valentine Willie – the first dealer to consistently place contemporary Philippine artists within a regional context – and Singapore Tyler Print Institute, which has increasingly included Philippine artists within its high-profile program, from National Artist BenCab to recent Asian Cultural Council recipient Lyra Garcellano. Further underscoring this phenomenon of ‘contemporary Philippine art’ as the pulse of Singapore’s market is painter Rodel Tapaya, who won the coveted Asia-Pacific Breweries Foundation Signature Art Prize (15.) for a painting blending Bontoc and Ifugao mythology with Tagalog folklore. It returns us to our axis of this discussion: geography, networks and demand.

Of other spaces:

Between 2000 and 2008, the number of Asian biennales doubled parallel to Asia’s growing prosperity and changing tastes; 25 of the 80 biennials held today are sited in Asia (16.). ‘What these figures apparently say is that participation has become more dependent on which artworld network is being tapped into and what particular curatorial bent, however incoherent, has determined how these events under scrutiny take shape’ (Legaspi-Ramirez 2007: 120). Add to that the growth of art fairs across Asia, a staggering 35 new fairs started since 2000, including Manila, as well as a phenomenal increase in Asian artists shown by non-Asian galleries.

These figures collectively say more about the ‘brand’ of Asian art and aspirations of these nations than antiquated curatorial models. It is not surprising then that this sheer volume impacts upon what is being produced. Asia’s newly prosperous and bourgeois ‘middle classes’ are not wholly determined by the 20th-century European and American (‘trans-Atlantic’) art markets that for so long have been the key metropolitan organizers and arbiters of taste of the modern art world system. Indeed, we are witnessing the rise of regional metropoles (e.g. Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Tokyo), and there are local, national and regional elites and emergent middle-class entrepreneurs seeking their own ‘distinction’ and expressing their tastes in the visual art scenes and markets.

Frankie Callaghan “425” (2009), from ‘Dwellings’ series, archival inkjet print, 68.6 x 102 cm; Image courtesy the artist and Silverlens

Perhaps a good example is the ‘hammer results’ for Philippine artists in the last five years. Ten years ago Manila’s art scene congregated around Megamall as the pulse of this scene. Today a gavel landing in Singapore or Hong Kong can have a seismic result felt in Manila. At Sotheby’s Spring 2011 Auctions in Hong Kong, Ronald Ventura’s (b.1973) painting Grayground hit a new world record for any contemporary Southeast Asian painting at US$1.1 million, a painting the catalogue described as ‘existential mash-up of hyperrealism and graffiti confronts viewers on how art should be’ (17.).

The year before at Christie’s sale it was Geraldine Javier (b.1970) breaking records. Her portrait of Frida Kahlo with framed insets of embroidery realized a new record at US$188,265, fetching ten times its estimate. As Javier caught the world’s attention, Filipino National Artist Fernando Amorsolo’s painting, Lavanderas (Washerwomen) dated 1923, was sold to a Filipino collector for US$433,992, and Rice Planting (1951) for just US$142,366. When you chart the results for Philippine Masters against works made in the ‘auction year’ by rising stars, it says a great deal about shifting tastes and value production, and the power of this global branding for contemporary art. As Lopa says, ‘young artists are hot commodities’ (Lopa 2011) and, dovetailed with the Ateneo Art Award, collectors are rushing to sign up on ‘wait-lists’ for artworks. This artificial market is skewing balance within Manila’s art scene.

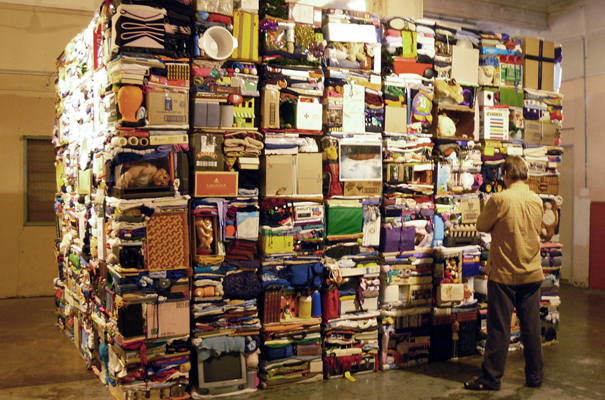

Alfredo Juan Aquilizan and Maria Isabel Guadinez-Aquilizan “Address (Project: Another Country)” (2007-08), Domestic objects cast on balikbayan (homecoming) boxes, sampaguita scent, Installation view Singapore Biennale 2008; Photograph Gina Fairley

To give us a further sense of what these shifts mean visually, I turn to the figurative painter Jose ‘Jojo’ Legaspi, and installation artists Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan. By 2002 Australia’s fourth edition of the Asia Pacific Triennial was grappling with its focus and the region’s rapidly shifting interests. It selected Legaspi (b.1959) as sole representative for the Philippines, a rather divergent image to the Philippine art it had previously exhibited – socio-political art had long been the darling of this biennale circuit. Legaspi’s introverted, explicit and probing images became the target of media scrutiny regarding the accountability of selection (18.), and yet the following year Legaspi installation for the 8th Istanbul Biennial, Phlegm (2003), was celebrated. His inclusion in the Inaugural Singapore Biennale (2006) with the provocative painting St Thelma, her skirt raised baring genitalia and fangs, illustrates the pace of changing attitudes towards contemporary expression within the region.

Jose Legaspi “Saint Thelma” (2006), oil on canvas; 122 x 214 cm; Image courtesy the artist and Singapore Biennale

Clarke argues that, ‘The commercial art world lurks in the shadows of the Biennales, since they are sites where reputations are established’ (Clarke 2002: 46). An interesting twist on this idea of the biennale as a new ‘shopping platform’ is the way the Aquilizans repeat their projects, altered slightly for local collaboration or nuance. They are almost selected from ‘off the shelf’, be it dreams tucked into blankets in Japan, Korea or Logan in Queensland, collected used-slippers from Singapore to provincial Philippines, or a Filipino jeepney set centre stage at Venice Biennale, a Brisbane commercial gallery and Centre for Asian art in Sydney – it is a mobile transaction. Conceptually read as an abstraction of ‘travel’ and ‘migration’, I am more interested in how the reading of their work is transported rather than the fact of their mobility itself.

The Aquilizans’ conjuncture with the Mabini painter Antonio Calma extends this point (19.). While Calma’s ‘tourist paintings’ make sense within the context of Manila, in the Aquilizans’ use of them, stacked in columns or hung salon-style with commercial proliferation, they become conceptual ready-mades that operate within a global realm of biennales and fairs, maintaining their commercial foundations and yet still recognizably Filipino in character. It is this trans-locational flex that defines contemporary practice today. And the making of their meanings continuously shifts in the local readings of artworks in each different setting and market.

Penetration – the new spin:

I started this article under the rubric of multiple geographies and shifting networks. Conventional understanding has moved to the position that there is no collective ‘Asian’ identity – the polar ‘East’. Similarly, ‘Philippine art’ cannot be bundled into one bag, and yet, there are traits that consistently brand it as undoubtedly Filipino. It draws on subliminal influences and social culture that well directly from the landscape of there, a unique recipe of religion, politics, density and history. It manifests, albeit it consciously or subconsciously, through the spatial understanding of the object and how elements are placed together. It is observed in the creative use of materials, a make-do spirit, technical prowess, flutter between kitsch, animism and humour, and I would posit as key – its urbanity. Like a Filipino Sari Sari (variety) store, everything is on offer, and it is this ‘skein’ that defines contemporary Philippine art.

It brings me to Poklong Anading (b.1975), my final case study, known for his dexterity jockeying mediums that explore the density of this city in constant flux. Like the Aquilizans, he intuitively taps into what could be described as collective residual memory, pre-occupied with the manner in which we look and how, through objects, cultural tangibility is mapped. Anading’s compulsion to collect and engage the everyday, fusing low technology in a high-end installation genre, can range from the most ephemeral act of collecting dust, to resin-cast rubbish as an aspirational metaphor, to the ‘ends’ of soap bars conflated into the sacred palm of Santo Niño with ‘soap on the rope’ humour.

Leeroy New “Balate” (2010), Detail of installation view Ateneo Art Gallery, electrical PVC tubing, cable ties; dimensions variable, Ateneo Art Award Winner; Image courtesy the artist and Ateneo Art Gallery

What is this Filipino-ness? It is an intuitive embrace of the object shared by many artists from Gabriel Barredo’s baroque kinetic sculptures, for example, to Leeroy New’s sculpture Balate (2010), constructed from cable ties and orange electrical tubing that consumed the façade of the Ateneo Art Gallery taking a stranglehold on authority, to Mark Salvatus’s landscapes from plastic drinking bottles, and Ling Quisumbing Ramilo using pencil and sandpaper assemblages fusing sentimentality, memory and intuitive aesthetics. This idea of trans-experience deals with how objects and artworks are re/configured outside the focus of a singular place. It is witnessed in Anading’s use of trapos, circular rags found on the streets sold as ‘wipers’ for maids, tricycle and jeepney drivers. Anading celebrates them in his installations Untitled (landmark) (2007) and Fallen Map (2007), where their patterns are painted on roadwork rubble placed flotilla-like within the gallery environment. Their designs echo geometric abstraction equally as the semantics of flags demarcating territory. This site/insight play is a strong Filipino tenet.

Working across all mediums, Anading rode technology’s evolution in the Philippines and the prevalence of the screen that drove contemporary art tastes internationally, producing and curating video works and founding the production company Furball. While video had little collecting currency locally, it gained traction fast during 2000s. Parallel to this was a swelling interest in photography nurtured by Silverlens (opened 2004), which has become an integral player in this contemporary scene: artists such as Frank Callaghan, Lena Cobangbang, Johann Espiritu, Kidlat de Guia, Wawi Navarroza, Neil Oshima, Rachel Rillo, Steve Tirona, Conrado Velasco, MM Yu, who with others form the fastest growing practice in sync with parallel trends across Southeast Asia.

The digital camera and more recently the smart phone have become ubiquitous, altering not only what is being produced but how it is being disseminated that in turn has the potential to alter the meanings of the artwork itself. Artworks are being documented and marketed resulting in greater professional practice and visibility of Philippine art. In that same recent time passage, a proliferation of blogs, social networking, and virtual curatorial platforms have become the ‘new alternative’, unbounded by territory. Hoskote observed this new technology-aided fluidity in the context of India:

First, it has underlined the need for new genres of visuality, so that the art object can hold the attention of viewers within the new frames of comparison, while maintaining its critical tenor. Second, it has … opened the so-far hermetic artwork to audiences proposing a new sense of community. Finally, it has exposed the myth of the universality of meaning by demonstrating the fragmentation of collective attention into specialist publics. … In effect, this means that Asian art must now prod into being a new public sphere, which is spread over material and virtual space, and involves both a sense of locality as well as that globality which is now inevitably parenthetical to the local. (Hoskote 2002: 87)

Two extremely interesting Filipino portals re-charting the paths of access are Visual Pond – founded by Clarissa Chikiamco and Rica Estrada and posting dialogues with artists utilizing youtube; and an initiative of curator Lian Ladia and writer Siddharta Perez, Planting Rice, which seamlessly connects Manila-based artists and a diaspora of Filipino artists (20.). Further to this virtual platform are subscription-based portals, Tricki Lopa’s extremely thorough ‘open door’ to this scene with her Snippets from the Manila art scene, Chabet’s blog utilizing Multiply, and the popularity of facebook as a marketing tool. For a country where travel remains an economic privilege, these portals have allowed Filipino artists to claim a sense of ‘place’ within a global art community. This ‘infoscape culture’ (Power 2010: 9) has become king.

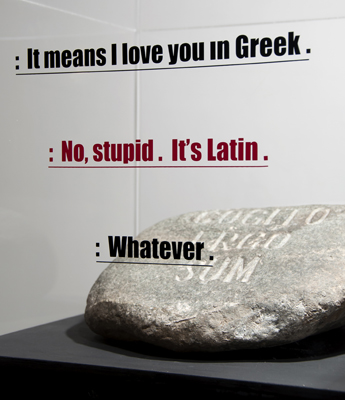

Cesare Syjuco “Greek to Me” (1997/2010), object composite in acrylic and wood vitrine; Image courtesy the artist and Galleria Duemila Manila

I want to finish these reflections with a work that captures superbly this idea of communication and currency – Cesare Syjuco’s assemblage Greek to Me (1997/2010). He’s etched a stone with the Latin phrase ‘Cogito Ergo Sum’, I think therefore I am, Rene Descartes’ foundation to Western philosophy (and, in the context of visual poetry, Barbara Kruger’s signature appropriation ‘I shop therefore I am’). Printed on a Plexiglas vitrine hovering in front of the object is the exchange: ‘: It means I love you in Greek. /: No, stupid. It’s Latin. /: Whatever.’ The contemporary apathy to read, to take the time to understand (or worse still, not to want to understand) is brushed off with the pun ‘it’s all Greek to me’ and the dismissive catch-all phrase ‘whatever’. Context is challenged by text – but also text is reinscribed in the artwork

When reading contemporary Philippine art within our regional and global context, we remain alert to the sway of the market and curatorial agency and the many locally-specific layers that bring this narrative into relief. This article has journeyed across Manila’s various art scenes that are parallel to a growing interest in Filipino art within the spectre of ‘contemporary Asian art’ that in turn responds to and is moving beyond transatlantic metropolitan art scenes and markets. The art landscapes are clearly changing. As pace and pulse skew and fracture Manila’s art scenes internally, criticality and the time to stop and translate current visual production are also vital functions that need to be carried out by outsiders and insiders alike. Visual cultures need their viewers to look both ways.

Notes:

- The first VIVA EXCON 1 was held in Visayas in 1990, led by the Black Artists of Asia collective (formed 1986) to promote contemporary dialogue among regional artists. It continues today. BAA member Charlie Co runs Orange Gallery Bacolod, a hub of regional activity today. The Baguio Arts Guild was formed in 1986 ‘in search of ethnicized forms to counter the abstraction fostered by art schools in Manila’; the Baguio Arts Festival started in 1989, a performance/installation based event steered by Robert Villanueva, BenCab and Santiago Bose. Tam-Awan Artist Village developed around the same time. Today the Baguio scene is dominated by BenCab Museum, and Kawayan de Guia curates the Victor Oteyza Community Art Space; Pinto Gallery Antipolo, hosted by patron Dr Joven Cuanang on Manila periphery, dates back to the 1990s. The National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) formed in 1992 to address arts across the archipelago. In 1995 NCCA launched Sungdu-an to even the field for non-Manila artists with a multi-regional thrust through exhibitions and research. The Philippine Journal of Visual Arts, Pananaw, started as an NCCA initiative in 1999. Its annual editions survey activity and issues from Manila to the regions.

- The Art Association of the Philippines (AAP) was established in 1948 and grew out of U.P. School of Fine Arts; Philippine Art Gallery was founded in 1950. Luz Gallery (1960–2002) is considered most influential in the birth of patronage and collecting. Galleria Duemila is the longest consistently running commercial gallery today. The first international biennale invitation was to the Second International Contemporary Art Exhibition, India (1953), followed by the Spanish-American Biennale in Cuba (1958), and the Venice Biennale (1962).

- After the first AAP competition (1948) debate by Victorio Edades and Guillermo Tolentio, published in the Manila Chronicle, which escalated to a dramatic walkout by the conservatives at a Rotary exhibition/competition in 1955, described as ‘a turning point for Philippine art’ (Ledesma 1974: 17).

- The First Asia Pacific Triennale Tradition and Change (1993) included Nunelucio Alvarado, Santiago Bose, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Brenda Fajardo, Juynee, Julie Lluch, Aro Soriano and Roberto Villanueva. Its second edition, Present Encounters (1996), included four Philippine artists plus the collective Sanggawa. APT3 (1999) included Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, Agnes Arellano, Roberto Feleo, John Frank Sabado. The Philippines was only omitted once.

- SM Megamall in Mandaluyong City opened in 1991, its 4th floor a dedicated Art Walk and space for hire, The Art Centre. The mall-located gallery has continued to be a strong part of this scene, though dwindling in the last five years as the top-drawer galleries have relocated.

- Shop 6 was founded in 1974 by Roberto Chabet, Yolanda Laudico, Boy Perez, Joe Bautista, Fernando Modesto, Rodolfo Gan, and Joy, and was located in Kamalig Arcade, Pasay City.

- Chabet: 50 Years, organized by King Kong Art Projects Unlimited, a non-profit artist organization supporting alternative practice. Survey partners included: Osage Art Foundation, ICA Singapore LASALLE College of the Arts, University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts, West Gallery, Finale Art File, Mag:net Gallery, MO_Space, Manila Contemporary, Galleria Duemila, Paseo Gallery, Ateneo Art Gallery, Lopez Memorial Museum, CCP. Asia Art Archive (Hong Kong) and the Lopez Memorial Museum co-launched The Chabet Archive digitization project (2009).

- To be continued coincided with Inaugural Art Stage Singapore (2011) at Marina Bay Sands. Chabet’s work was cited as the ‘freshest discovery’ despite its non-commercial, conceptual position. Across town Manuel Ocampo had his first exhibition in Asia at Valentine Willie Singapore and BenCab showed at Singapore Tyler Print Institute. Singapore is the primary regional market for contemporary Philippine art.

- Ateneo Art Gallery Collection is focused towards Modernism, only recently collecting contemporary artists, largely winners of its award. Singapore Art Museum, established 1976, was the first institution in Southeast Asia with international standards and a mission to preserve and present the contemporary art of the region.

- Freies Museum Berlin, October–November 2010. ‘Inversion of the Ideal’ at GZK included Poklong Anading, Lena Cobangbang, Gaston Damag, David Griggs, Robert Langenegger, Manuel Ocampo, Jayson Oliveria, Gerardo Tan, and MM Yu alongside Austrian artists. These artists continue to be represented by GZK, Graz Austria.

- In his publication ‘Northrop Frye: The Theoretical Imagination’ (1994: 12), Jonathon Hart cites David Cayley Northrop Frye in Conversation, 1992.

- An initiative of the Australian Government, The Australia Centre Gallery Makati opened in 1992 and was a key player in this scene for both Filipino and Australian artists.

- Email interview of author with Norberto Roldan, August 2006

- Organized by Philippine Embassy in Singapore in partnership with local galleries; has showcased more than 200 Filipino artists since 2007.

- Asia-Pacific Breweries Foundation Signature Art Prize hosted by Singapore Art Museum, announced November 2011. Prize was SD$45,000.

- Asian Art Archive (Hong Kong) research portal published in 2008 (http://www.aaa.org.hk/onlineprojects/bitri/en/index.aspx), German-based Universes in Universe have consistently documented these events (http://universes-in-universe.de/english.htm), and Pananaw 6 (2007) charts Philippine inclusion in biennales.

- http://artradarjournal.com/2011/01/05/most-successful-young-visual-artists-in-manila-named-by-spot/

- Some Australian newspapers attacked government support of ‘degenerate art wallowing in misery’, throwing into crisis the APT’s accountability to audiences.

- Mabini artist is a term for low-brow kitsch tourist paintings sold around the Ermita precinct, Manila, a history that stretches back to the 1950s.

- Visual Pond (http://visualpond.multiply.com/journal), Planting Rice (www.plantingrice.com) and Snippets (http://manilaartblogger.wordpress.com/).

References:

Ching I (2010) Tracing (Un)certain Legacies: Conceptualism in Singapore and the Philippines. Hong Kong: Asian Art Archive Dialogue (http://www.aaa.org.hk/newsletter_detail.aspx?newsletter_id=1045).

Clarke D (2002) Contemporary Asian art and its western reception. In: Site + Sight: Translating Cultures. Hong Kong: Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore, 45–49.

Cruz J (2005) Transitory imaginings. PANANAW 5: Philippine Journal of Visual Arts, Philippines: National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 18–29.

Cruz J (2010) The spaces in between. PANANAW 7: Philippine Journal of Visual Arts., Philippines: National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 47–51.

Godfry T (2011) Roberto Chabet. Posted 2011-05-09, C Arts, Volume 19 (http://www.c-artsmag.com/betac-artsmag/index.php/articles/view/173).

Hanru H (2007) 10th Istanbul Biennial press statement

Hoskote R (2002) India ink, Manila envelope: Three meditations on art and the global media. In: Kataoka M (ed.) Under Construction: New Dimensions in Asian Art. The Japan Foundation Asia Centre

Labrador A (2005) Where in the world are you from? Negotiating processes of distinction in international art spaces. In: Tsoutas N (ed.) Knowledge+Dialogue+Exchange: Remapping Cultural Globalism’s from the South. Australia: ARTSPACE Visual Art Centre Ltd., 101–114.

Ledesma PK and Guerrero A (1974) The Struggle for Philippine Art. Philippines.

Legaspi-Ramirez E (2007) Investigating circulations: The folly of [art] bottom-lines and number-crunching. PANANAW 7: Philippine Journal of Visual Arts, 114–123. Philippines: National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Lopa T (2011) The new masters. Posted at: http://www.surfaceasiamag.com/art/462-the-new-masters October, Philippines

Maravillas F (2010) The poetics of the uncanny: Art and home in the age of mobility. In: Last Words. Australia: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 12–17.

Ocampo M (2010) Curatorial note. In: Bastards of Misrepresentation: Doing Time on Filipino Time. Berlin: Freies Museum.

Power K (2010) The world we live in. In: Bastards of Misrepresentation: Doing Time on Filipino Time. Berlin: Freies Museum.

Rogoff I (2003) From Criticism to Critique to Criticality. Posted on European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies (http://eipcp.net/transversal/0806/rogoff1/en).

Supangkat J (1996) Contemporary art: What/when/where. The Second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art Catalogue excerpt. In: Choy LW (ed.) A Taste for Worms and Roses Australia: Artspace Critical Issues Series 7.

Villegas RN (2010) New records set for Filipino art at Christie’s auction. Philippine Daily Inquirer, posted 06/07/2010 (http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/artsandbooks/artsandbooks/view/20100607-274208/New-records-set-for-Filipino-art-at-Christies-auction).