Egan Frantz @ Michael Jon Gallery, Miami

Michael Jon Gallery decided to launch its new gallery on the eve of Art Basel with a body of work by Egan Frantz. The choice of a young artist from Brooklyn is indifferent in the scheme of things. The gallery has a modest stable of just seven artists; none are Miami based.

While that may stimulate certain conversations, rather there are two things going on here, which I find fascinating as an observer to this art landscape: location and lexicon.

Topography is a Miami preoccupation – physically and psychologically.

Where a gallery throws roots in this local dervish, one might argue, defines it more so than its roster of artists – at least from the outset. That frame immediately ascribes the point of “check in” or “check out”. Simply, geography is more than just place; it states where on the pendulum swing one chooses to sit between the extremes that define Miami.

Michael Jon Gallery joins several galleries in a recent shuffle of Miami’s art landscape: after a decade, David Castillo has moved from Wynwood to an “off-street” space on Lincoln Mall; Frederic Snitzer has also moved from Wynwood to a rather isolating location in Downtown; while ructions within MOCA have seen the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) launch its statement within the hotbed of the Design District – complete with architectural plans and site locked down for its next step. Such moves are always considered.

Capitalizing on the “December moment” – when the international art world has its sights on Miami for a fleeting week – this positioning is key in badging the local gallery sector.

So how, then, do we read Michael Jon Gallery’s decision to largely stand alone in this landscape?

The Space:

This is the third venue that Michael Jon Radziewicz has taken on in the past three years, and second with business partner artist Alan Gutierrez. And, with a satellite venue in Detroit opened last fall (2013), the gallery is striding at a bold and feverish pace.

Located in what could be described as a tract of semi-industrial space on the edges of Miami’s Little River business district (NE 69th St) – notably opposite the McArthur Dairy factory with its slightly acrid aromas keeping the neighborhood “real” – Michael Jon Gallery is defining its own territory.

There is an odd simpatico with the company’s marketing tag: “We all grew up on McArthur” – a kind of honest embeddedness that takes a different tone to the contrived fabrication reserved more generally for art neighborhoods.

Things are brought into sharp contrast. It may have something to do with the ultra-high lux that saturates the space, its excessive banks of fluorescents making this white cube bristle with a tone of hyper-reality. Or perhaps it has to do with the clean hang and erudite formalism of this inaugural exhibition. Either way, it is a different surface shine than the usual Miami stereotype of laid-back “island time”.

Radziewicz makes no excuse that he is a dealer. He does not try to weave a narrative as a kind of jockey between the edge and the mainstream. He wants to place art.

Speaking with him last week he said: “It is not advantageous to be great salesmen. They will just take this thing home and think it’s a turd, and then send it to auction. That helps no one.”

Adding, “We would both feel weird if we were aggressive.”

Gutierrez quipped: “Our sales approach is not having a sales approach.”

“We do a really good job and go to bat for out artists,” reassured Radziewicz.

And when asked why “there”, now, Gutierrez laughed, “We went rogue! While it is exciting to be part of the art communities, at same time it’s nice to remove yourself from any implications. Now we can concentrate on the inside – not the outside.”

Radziewicz’s simply added:

We are a destination gallery. People are going to come to us; they are not just going to stroll in off the street.

How, then, does this inaugural exhibition drive traffic and, indeed, define the gallery’s path forward?

It remained a perplexing question for the two dealers. So let’s attempt to unpack Frantz’s show to try to unravel the answer.

The Show:

Egan Frantz has been repeated quoted that he, “rejects the belief that reality can be captured in language.”

So the leading question, then, is “what language are we speaking?” And, if the title is any hint of direction, it is a field of banality and subturfuge: Monday and Friday, Tuesday and Friday, Wednesday and Friday, Thursday and Friday, Friday and Friday

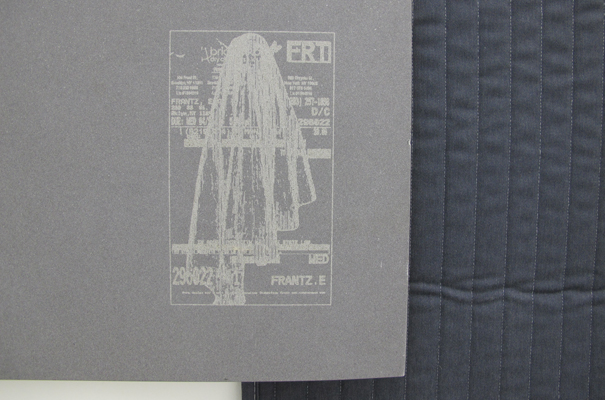

Walking into the gallery the viewer is presented with seven works that hopscotch between the composite pairing of a panel and a shaped textile field, and a single panel painting emblazoned with a stamped dry-cleaning receipt. It is a reductivist consideration – or is it?

It immediately takes on the vernacular of formalist abstraction with a minimalist reverence. And, yet, counter to both positions is an inseparability from the object.

The object takes on a structural role here. Radziewicz explained the attraction to Frantz’s work for its architectural frame – the protective linings used in elevators flattened out to a 2-dimensional plane in conversation with the gallery’s own clean adherence to form and function.

It’s what we would call a “no brainer” for its eloquence, however, remove the connective trigger and what are you left with?

Reading this work as an Australian – where this elevator vernacular is not ubiquitous – the eye strays to other visual connections. Perhaps, it is the sewn line on these blankets that echo chalk-stripe suits – the language of stock markets – hinting (with an uncanny parallel) to the aspirational verve that speaks of this “art fair moment”? After all, doesn’t the elevator move up and down?

Or maybe it is the language of shipping blankets – art handling – and notions of preciousness attached to the constructs of value? Which, if one should desire to mine meaning (a current preoccupation in art rhetoric) we only have to let our eye drift toward their “stamped” tag – a manipulated dry cleaning receipt that finds its way to each panel’s lower quarters.

Navigation is where criticality lies.

Frantz has made no secret that his interests dwell in the realm of speculative realism. It locates the object within a place of deeper contention. That such debates should occur, or are sited within, the art fair moment – not to mention a redefinition of a gallery through a new space – I find incredibly interesting.

Am I reading too much into such serendipity? The choice of Frantz would argue, no. It is, however, a Miamian question. What do such re-shufflings – and articulations – of the geography mean? And is it merely a savvy re-application of a blanket to protect an elevator, or do we take Frantz’s cue to delve deep here?

Gutierrez summed it up: ‘The more I think about this show the less I understand, which is a good thing. I think that is Egan’s intention. It is not bombastic but it is bold and interesting and weird. It is a questioning show.’

So Monday, Wednesday, Friday…who cares? It is all a blur at this time. Perhaps this is what makes this particular exhibition – and choice of artist – so interesting in the climate of a new gallery space and Miami fair mania.

Egan Frantz: Monday and Friday, Tuesday and Friday, Wednesday and Friday, Thursday and Friday, Friday and Friday

22 November – 17 January 2015

255 Northeast 69th St, Miami, Florida 33138