Beyogmos: Mai Nguyen-Long

LABORATORY FOR LABELS:

As human beings we have an automatic compulsion to assign ‘things’ a place, compelled to tether a person and their actions to prescribed labels as a mode for navigating unknown territory. Simply, we hijack the identity of others by inserting it within our own cultural frames of reference.

How, then, do we digest the artworks of Bulli artist Mai Nguyen-Long, which both bridge and contest those very assignations?

Bundled up with many artists of her generation working across cultural memory, once removed and somewhat fractured, this imposed multi-cultural frame has aided the identity confusion felt by Mai and others. Born to a Vietnamese father and Australian-Irish mother, and having spent her earliest years in Papua New Guinea and the Philippines before studying in Taipei, Hanoi and Beijing as well as Australia, Mai fits more comfortably within contemporary definitions of the peripatetic artist less reliant on geography. As she described,

“I’m trying to create a legitimate space, a tangible space in the gaps where things cannot be grasped or defined, a space between definites.”

It is a kind of ‘non-labelling’ in sync with the words of Cuban curator Gerardo Mosquera: “More than invent[ing] new terms, the existing ones recombine and recycle, in a spirit of re-adaptation, with meaning concentrated less in words than in the connecting dialogical, transfiguring space of the hyphen…it unites at the same time [as] it separates.” 1.

Turn then to this exhibition Beyogmos, a pseudo laboratory for cultural dissection and classification. The word dissect means ‘to cut and examine in detail’. Acts of dissection and violence have remained central to Mai’s practice from her early abstract paintings of anonymous forms – several of which extend the breadth of this exhibition – to her performative burning of the sculpture Godog in 2009, a gesture of erasure of the politicisation of her Vietnamese identity.

In the same vein Vessel (2013), a carcass of a dog splayed open in jewelled splendor sits central to the gallery and anchors this exhibition. It feels ritualized. Is it an offering, autopsy, or metaphor for self-evaluation? We go into overdrive as our cognitive processes try to locate or assign meaning. Like Mosquera’s hyphen, it occupies a place where the altars of science and belief merge, uniting and dividing audiences through its most guttural of confrontations – reaction before thought.

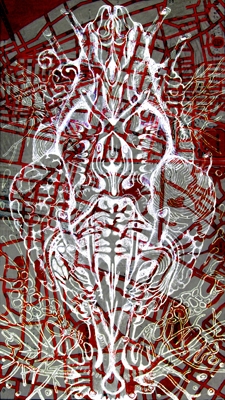

We should not be surprised by the inclusion of such an object. Mai has long honed in on the dog as a metaphor for her background or ethnicity. Vessel points to this past but also pushes forward, “going beneath the skin”, as Mai describes, to the place where truth perhaps lies. It is a departure in the work that has pushed Mai to new mediums, key of which is her drawn animation Beyogmos.

It is a logical next step from Mai’s drawing practice, the day-to-day psycho emotional journeys and desire to understand these within a broader social-cultural context. Mai explains, “For me, drawing is making the intangible tangible, but the charcoal drawing process for Beyogmos was more like returning that grasp to the intangible.” She continued, “The act of creating then erasing the drawing right away, with only the camera to rely on as a record-keeper created an emotional tension in me. I wanted to hold the drawings but I could not. I just had to continue drawing or I would lose the flow of thought.”

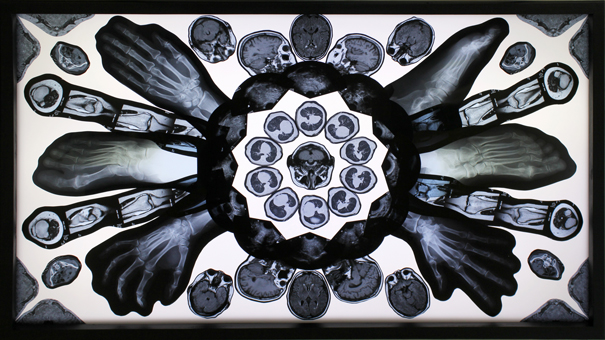

The animation’s soundtrack explores her father’s relationship to his culture of origin and how that genre of music permeated her growing up. It sits in contrast to Mai’s relationship with her non-Vietnamese heritage explored through the lightbox work, Maternal Doily, where she has collaged her own x-rays with those of her grandmother and mother. Pondering the interrelatedness of three women she asks, “Can we ever really escape ourselves?”

The doily as a symbol of domesticity builds claustrophobia in Mai, an inescapable genetic cycle, but when read as a Mandala or fractal it turns that specter to spirituality or science. Mai says this new group of works is looking for emulation where wonder and the sublime can co-exist. She continues, “it is about reclaiming, reconstructing and re-telling what has been torn apart; disparate parts and stories come together through collecting and observing, like a single slide under a microscope explaining a much greater whole.”

These ideas most literally unify in her installation Specimen (2013), stacked glass vessels containing found objects that present as new deviations for consideration. They recall scientific systems of categorisation and labelling, and yet this array of objects flutters between feeling familiar, valued, authoritative, and yet are clearly ‘not quite science’.

Often her specimens are tagged with ‘meanings’; the ritual of scraping off the jars’ original labels neutralises their mass produced branding. Mai described, “How we see the world can be overly dictated by labels and this can permeate our homes, how we think, hear, smell and function. It can be a blinding mechanism. Through this process I am discovering that the idea of labelling is liberating. But for cultural labelling to be useful it cannot be a means to an end in itself. It must be both robust and porous. It must continuously be seen in new contexts, prodded, questioned, opened up, and pulled apart again and again.”

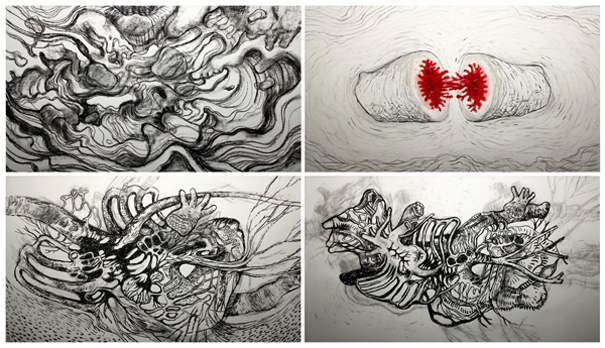

She plays out the slippage between ascribed knowledge and mythology, finding new expression in classification systems established by other means: memory paths, bodily fluids, emotional maps, and hybrid species. It is a similar fusion observed in her painting series Innersphere (1998-99) and the later multi-panel work Mis/alignment (2013) (pictured top), abstracted forms that morph in and out of familiarity. Are they plant forms, body parts, sexual perversions, or all simultaneously?

We can start to understand this feeling of physiology, of progressive connectivity. Mai intentionally plays out the tensions between logical expectation of order and a discombobulated sense of “wholeness”, as imagery taken from dog and human anatomy cross panels seemingly arbitrarily, at times stubbornly interconnected and at others mismatched like broken thought patterns, “drawing them out as landscapes and alien entities in their own right”, described Mai. It is a spatial metaphor for Mai’s relationship with the physical world.

“Veins become rivers and flesh the earth; a mapping of the universe. Brains get confused with genitalia and hearts get directly connected to brains. They form nondescript masses of micro macrocosms, patterns, shapes and forms. The process involves a tension between the observed and functional forgetfulness.”

You can start to understand how considered and layered this exhibition is, mapped across time, place and memory and, yet, there is a universal aspect to this exhibition that rubs shoulders with Mai’s very personal investigations and, in that, it is open to the viewer finding their own narratives co-existent within the work.

Beyogmos: Mai Nguyen-Long was presented at Wollongong Art Gallery 28 February – 25 May 2014. Wollongong is located about an hour south of Sydney (Australia).

Three of Mai’s works from the exhibition have entered the collection of the Wollongong Art Gallery.

Essay notes:

- Rhana Davenport quoting Gerardo Mosquera in “Beauty, Shadow-play and Silhouettes”, Art & Australia, Vol. 44, No.2. Summer 2006, pg. 242.

- Dialogical: written in the form of conversation; relating to dialogue.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.