UnBound, Yuchengco Museum Manila

BOUNCE:

UnBound (Yuchengco Museum, 24 January-20 February 2013) explored how culture can move beyond physical boundaries and the cartographic disposition of nation-based exhibitions and pre-packaged notions of exchange. Using the loose metaphor of the airport transit lounge as a zone of intersection – for coming and going, notions of home and away, transience and permanence – this exhibition took its cue from a group of artists and their self-driven desire to embed their practice regionally. What sets these artists apart is that they constantly oscillate between the Philippines and Australia, identifying with both as home.

In curatorial circles we like to ascribe to these peripatetic tendencies as a contemporary phenomenon resulting from our increased global mobility. Our world is shrinking and our capacity to bounce between locations has become unbounded. It promotes a hyphenated identity that throws up fresh thoughts on how we define concepts such as assimilation, belonging, memory and movement in our times.

French Philosopher and Social Theorist Michel Foucault was ahead of his time when in 1967 he described, “…we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by- side…We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.” (1.)

What is interesting in Foucault’s vision is this culture of collective connections. Key to its success, however, is the individual desire to reach out and make it happen? For UnBound, I turned to six artists whose prolonged activities bridge a Filipino Australian experience.

They offer an alternative and, arguably, more realistic picture of exchange today that “is more critically attuned to the complexity and dynamism of the relationship between modes of belonging and practices of communication.” (2.)

For these artists the rhetoric of ‘place’ and ‘identity’ is of less concern than the intuitive connections their movement brings, from the literal passage of an object or artwork, to questioning how histories are carried and rewritten responding to different criteria and value constructs. Simply, these artists carry with them their own visual language that forms their frame of reference.

Brisbane-based husband and wife team Alfredo & Isabel Aquilizan return home to Manila to fabricate their work. ‘Made where?’ is a blur mirrored by the fact that the Aquilizan’s are considered both Australian and Philippine artists. 2013 marks 20-years of Tony Twigg coming to Manila and, having presented a dozen shows here, his work has had an impact on some young artists and is held within major collection. Could it then be Filipino?

Diokno Pasilan’s bounce is equally as long. He was involved with the Australia Centre as a host for visiting artists when it opened in the early 1990s. This is where he met Tony Twigg. He received his Diploma of Fine Art from the Western Australian School of Art and now lives between Melbourne and Palawan. He remains active in both art scenes. Juni Salvador (who takes his citizenship oath on this coming Australia Day, coinciding with this exhibition) lives across Sydney and Manila, where his art practice remains embedded – his studio is his childhood home, whereas the ‘home’ of his family is in Sydney.

David Griggs in recent years has made Quezon City his home, often working collaboratively with local artists and billboard painters, but more importantly has been assimilated into a group of contemporary urban Filipino artists – the Bastards of Misrepresentation – shown internationally from Berlin to Austria and New York. Maria Cruz’s career began in Manila, moved to Sydney where she has exhibited and taught, returning to Manila en route to Berlin.

All six artists have been instrumental in taking the work of Filipino artist’s abroad, and Griggs, Twigg and Pasilan have run independent alternative art spaces nurturing a bilateral cultural dialogue. It is a very conscious and sustained activity that these artists practice, and they have continued to build upon the foundations laid by the Australia Centre during the 1990s.

In 1992 the Australian Embassy Manila embarked on a pilot cultural program, a venue where Australian and Philippine artists and audiences could come together. Known as the Australia Centre (3.) its inaugural Director was Jeannie Javelosa, now Curator at Yuchengco Museum. It came at a time when museums and governments internationally were shifting their attentions to more peripheral and regional dialogues. We witnessed a boom in biennales, artist-run spaces and the travel of curators on the prowl for new perspectives. In the Australian context this lead to events such as the Inaugural Artists’ Regional Exchange (ARX, Perth 1987), the formation of Asialink (1990), the Inaugural Asia Pacific Triennial (1993), and the expanding of the Australia Council’s artist residency studios to include a short-lived one in Malate. Curators from the Queensland Art Gallery travelled to Manila and worked with local industry professionals to select artists for this first APT, a somewhat radical initiative at the time, artworks that were then previewed to Filipino audiences at the newly opened Australia Centre.

At a policy level, a Cultural Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines was ratified in 1980. (4.) The most recent chapter of policy falls under the watch of current Prime Minister Julia Gillard with the recently released Australia in the Asian Century White Paper. ‘The paper calls on all Australians to boost their understanding of our region’s history, culture and customs and lays out a series of pathways for Australian arts, artists and cultural institutions to play a pivotal role in building our relationships and networks across our region.’ (5.)

This exhibition cames in the wake of that decision and on the occasion of Australia Day. While these policies and institutional initiatives define the national mind-set, one might ask is it the real picture? UnBound attempted to reconcile those ideas, today.

DEPARTURE : IDENTITY

This cultural dialogue between our countries started much earlier than statistical figures, policy, or institutional programming. Ian Fairweather was a British man who spent most of the 1930’s travelling through Asia before making Australia his home. He stopped for a while in Davao, Mindanao, in 1934 living at Piapi with Moro sea gypsies. It was the life around him he painted. From there he returned to China where he had been living. When the success of his first Philippine-subject paintings at the esteemed Redfern Gallery in London led to the offer of an exhibition, Fairweather decided to return to “the Islands” to paint it. Fate found him in Manicahan, near Zamboanga, in 1936 and then Manila where he stayed 21 months. He produced a small suite of paintings that were sent to Melbourne. They have since become the masterpieces of Australian Post-impressionism.

Fairweather’s restless life continued until 1952, when he settled in Australia and began painting large-scale works. Anak Bayan (1957) was the first of these large-scale works that came to place an abstract sensibility tutored in Asia at the heart of modern Australian painting. Ostensibly it is a painting of a Manila street scene and its title – slang for ‘the people from here’ – illustrates his socio-ethnographic understanding of this place. (6.)

Tony Twigg’s installation Anak Bayan (again) plays tribute to that history as the foundation for this exhibition. Painted in the tradition of Philippine billboard artists, this ‘copy’ is presented with the original Art Gallery of New South Wales didactic text for the artwork (which is factually incorrect) and Twigg’s correction of it. The painting is a prized piece within gallery’s collection. Twigg’s facsimile installation is interesting from two positions: Identity and authorship become rubbery secondary to the dialogue its content offers. It is a painting of nationalistic Filipino subject matter, adopted as an ‘Australian masterpiece’, only to return to its source as a copy – a fake. Furthermore, it speaks of the invested mythologies and inaccuracies of written art history set against the incisive and intuitive observations of the artist, condensed and distilled from the culture at large. Anak Bayan offers a thread that connects this group of artists and, indeed, encourages dialogue about what drives contemporary art making in this region today. Simply, it is a search for truth.

UnBound attempts to draw those connections across time and classification from Fairweather’s ‘Phil-Australian masterpiece’ to the Aquilizan’s stacked ‘Mabini’ paintings, commercially viable both as a local tourist product and conceptual-toned contemporary artwork on the international stage, to David Griggs’s lyrical portraits, discernable as Australian for their unmistakable reference to Sidney Nolan Ned Kelly series and yet to a Filipino they don’t immediately read as ‘Australian’.

Titled The cowboy paintings, Griggs interrogates the ethnographic role of the portrait and its veracity when transported out of the context of Australia, where this genre is deeply revered. Perhaps it has something to do with the mythology of the bushman, the larakin, or how we encounter the vastness of the land in which we live. Placing that psyche in Manila where the portrait slips into a different space and sensibility, from a picture of nationalism to the photorealist fashion of the art market, the points of reference are unbound from convention or history.

Griggs’s has long been interested in the appropriation and the adaption of culturally specific images. It has been a two-way street charted less along a multi-cultural frame or colonial position and more from the perspective of ambiguous authorship, often working collaboratively with Filipinos. Like the mestizo his artworks blend and blur their location and colonial stance. We are forced to consider them by alternate criteria. Simply his ‘cowboy paintings’ explore the way residual images, historiographies and mythologies are carried with us to new frontiers. Researching for this exhibition I came across an early video work by Tony Twigg, its soundtrack stating, “We seem to arrive at places twice, first in space when we name the destination, and second in time when our destination names us.” (1995).

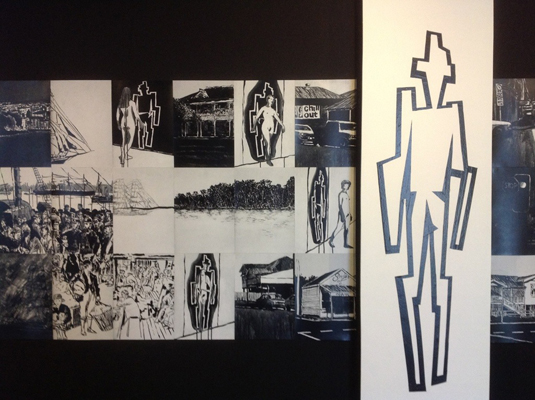

I have deliberately placed another ‘facsimile’ adjacent to the Fairweather* installation. It has an uncanny parallel to Anak Bayan, both processional narratives that observe a landscape. In 1995 Twigg presented the exhibition A Shadow in My Tree at the Queensland Art Gallery, a collection of paintings, constructions, video and performance-based works that explored migration, arrival and assimilation. Central to this exhibition was an installation of 188 painted panels dissected by an abstracted timber figure. It came at the cusp when Twigg’s work was shifting from figuration to a more universal abstraction and perhaps a departure from the constraints of identity.

Reworked for UnBound the original panels have been edited and digitally printed and the sculpture has been extracted as a stencil to be drawn directly onto the gallery wall, playing off built and imagined space. As a linear sketch it is not so dissimilar to a forensic line, drawing the viewer into the centre of the narrative at a human-scale. It is not so much reliant on exactitude but rather speaks of a recreation of the self that comes with migration and movement. It is this essence that has informed Twigg’s later constructions using found objects. Australian curator Felicity Fenner says of the Aquilizan’s work, “Always in flux, one project evolves into the next, adapting to new contexts as it shifts between countries.” She continued, “they create work that is informed by the struggle of displacement, but also advantaged by the bird’s-eye view afforded by seeing one’s place of origin from the distant perspective of another place.” (7.)

It is true also of Juni Salvador’s installations drawn from his Living the Cliché series. They role-play the stereotypical experience of the immigrant: Untitled (family portrait), a tourist snap overlaid with equally clichéd ‘aboriginal dots’; Those who wait... the artist’s family tree of framed certificates of Australian citizenship; and Boomerang…neither here nor there, where the contents of one’s domestic environment collectively define their identity. Salvador strips expectation down to the most banal reality – the cliché.

Maria Cruz similarly calls on aspects of popular culture isolated and stripped bare to its most raw connection. Characteristically using text capitalized and without punctuation – be it the song titles of Yoko Ono, ‘sari sari’ signage or phrases plucked as puns – her interest is in nuances of text as it overlaps, fuses and blurs across localities and cultural translations. In a rare pairing of her own image with text, the painting Maria (1997) dwells in the realm of nomenclature, its strident identification almost obliterating the persona. Cruz literally asks, “What’s in a name?” “How do we construct who we are?” This painting won Cruz the prestigious Portia Geach Memorial Award in 1997, one of Australia’s three most important prizes for portraiture.

Like Cruz’s self-portrait, Diokno Pasilan’s Senior Citizen series most literally takes on the construction and authority of identity. Working with aged residents from a small Palawan community, and later in Daet, Luzon, Pasilan photographed seniors arming them with a valid I.D to apply for health care. The sitter’s eyes hold ours, clouded by cataracts but firm as their witness to who they are. Is it fear in the grip of Alzheimers or anonymity as we fade from this world?

Presented as inkjet prints they are over laid with the artist’s poetic memories of home recorded from a distant town, Perth. Written in tea and coffee the text plays off the fragility of aging with their materiality.

“The repeated use of memory through the use of objects, icons, and language has concurrently allowed artists to insist on their identity [be it Filipino or Australian] and to inject a new shade into the definition.” (8.)

Sitting in the archives of the Museum of the Filipino People is the Manunggul Jar (890-710BC), a Neolithic burial urn excavated from Palawan. Considered a ‘national treasure’ this object not only carries histories both personal and collective, but as an object conveys a narrative. A small boat on the vessel’s lid ferries its oarsmen to the spirit world – the afterlife. In a similar way Diokno Pasilan’s Memory Boat (2011) connects with his childhood memories of his father, a boat builder from the Santo Nino area in Bacalod, Negros.

Constructed from timber venetian blinds discarded on the streets of Perth, their elegance is re-found in the nostalgic craft passed from father to son. Most of the artists in UnBound share Pasilan’s examination of transportability from the literal position of the physical passage of the object.

EXCHANGE ; OBJECT

Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan have long been interested in the ideas of relocation and temporary homes. As they explain, “we create our own reinterpretation of history (migration) through a fabrication of an object and the collection of narratives that go with it.” To do this they have turned to found objects such as balikbayan boxes, chinelas, household hand-me-downs, and in recent years have worked with Mabini painter Antonio Calma.

Mabini Artist is a term for the low-brow kitsch tourist paintings sold in Manila’s Ermita precinct, a history that stretches back to the 1950s. Placing them in stacked columns, arranged as installations or placed in vitrines, the image is either hung salon-style with commercial proliferation or turned in on itself rendered void. As Curator Joselina Cruz described, they are ‘translations from folk exotica to clever conceptualism’ at home and conversant within the domains of the biennale, art fair and international art museum. How then are these local paintings read when re-contextualised outside their specific locale? Simply they question how we construct value, navigating the ‘real’ within the hyper-reality of the global art world.

Moving to Sydney with his family in 2007, Juni Salvador started looking for a connection with that place. It seemed natural to turn to the ‘op-shop’ rather than the art supply store to find his materials. This is where he found his iconic boomerang (an indigenous Australian flying toy that follows a path back to its place of origin) complete with its $5-sticker. How do we read such objects: as discarded treasure, as throw-away culture, commercial cliché, or an erudite metaphor of the artist, constantly moving between here and there? Photographed over a year and randomly thrown up in this slideshow, one location is hardly distinguishable from the next. This overlapping and layering of images is like memory itself, recurring and reshuffling in our everyday. It is a complex psychological and sentimental state rather than merely the description of a physical location.

Twigg takes a slightly different approach to the object. Rather than a vessel for memories or storytelling, he believes the found object breathes with a universal humanity, relieved of placepolitics or nationalistic verve. For Twigg found branches, shipping palettes or market crates present material rich in patina, which he then assembles and paints as abstract forms, allowing the history of the timber to retain its character. He has said that working with found material ‘is like jamming with another person; you have to respond to something that has already been said’. It is not so dissimilar to the Aquilizan, Griggs and Pasilan practice of collaboration with communities, however in Twigg’s case it remains anonymous. His wall sculpture 2 sticks Pasay (2010) is a reconfiguration of crates found at Pasay palengke. His Filipino Found Object (2006) was a broken Santo resurrected from Blumentritt and co-joined with the very fabric of this society, its urban detritus. It has an uncanny parallel to Salvador’s boomerang both discarded spiritual objects.

This abstraction of the object goes further for Twigg and this is where his work differs significantly from the Aquilizan’s, Salvador, and Pasilian, in that there is no desire to retain the integrity of the narrative or memory that the object holds. Rather it is the integrity of the form and its energy for a place, allowing it to slide into a more ambiguous and individual connection with audiences that Twigg seeks. This is quiet literally played out in his Painting from the Filipino found object 2 (2006), where the object is literally used as a stencil. The tangible ‘voice’ of the form moves across mediums, and from 3 to 2 dimensional space. It remains visually familiar yet has become duplicitous and enigmatic.

It brings us to our final vernacular for exchange: abstraction. Just as the painted stencil stood in for a figure in Twigg’s re-created panel narrative, or the Filipino object in this painting, with the actual object removed the viewer is reliant on a set of constructs to form its image: knowledge, description, perception, instructions. Through its very removal it questions those systems of evaluation, and furthermore when recreated from a set of instructions or abstraction it forces us to engage with how cultural material is transported and translated.

Maria Cruz shares this interest in abstraction, and there is a deep compatibility between her work and Twigg’s. This is surprisingly extended to a new work by David Griggs in this exhibition, which echoes the shard-like motifs of Cruz’s recent X paintings. Cruz has increasingly turned to abstraction in her art making as a way of moving between places, proposing broader points of connections. Travelling with the baggage of nationalist narratives can skew our reading of place and engagement. UnBound offers a broad range of alternatives.

While this exhibition subtly interrogates geography as a weighty sign-system, it also attempts to liberate how we locate and identify artists – and ourselves – in relation to their movements and landfalls. Using Australia Day as the punctuation point to pause and consider this bilateral cultural dialogue between Australia and the Philippines, one can only be heartened by its legacy and optimistic for its continued future.

UnBound was commissioned by The Australian Embassy, Manila in partnership with the Yuchengco Museum, Manila (The Philippines), 23 January – 20 February 2013

Artists: Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, David Griggs, Ian Fairweather*, Juni Salvador and Tony Twigg.

Essay notes:

- Michel Foucault. “Des Espace Autres”, French Journal Architecture Mouvement Continuité, October 1984, lecture March 1967, “Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias”.

- Francis Maravillas. “The Poetics of the Uncanny: Art & Home in the Age of Mobility”, Last Words, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2010, p. 13

- The Australia Centre closed with the relocation of the Australian Embassy offices to Makati’s RCBC Towers in 2003. Its lifespan was just on a decade.

- The Cultural Agreement was reached on 15 April 1977 and ratified by both Governments 28 January and 20 February 1980, Treaty Series 1980, No. 9, Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Launched 9 October 2012; sourced 13 January 2013, http://asiancentury.dpmc.gov.au/white-paper

- Paraphrased from Tony Twigg’s research notes with permission.

- Felicity Fenner. “Tallstoria”, In-Habit: Project Another Country, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney, 2012, p 91.

- Joan Kee. “Balancing Act: Tension and tenacity in Asian American art”, ART Asia Pacific, Issue 20, 1998, pg 68-75.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.