Conflict over copyright – is it fair?

The arts sector is deeply divided over the introduction of fair use into the Australian Copyright Act, as was evident during the VIVID panel discussion on copyright in the digital economy.

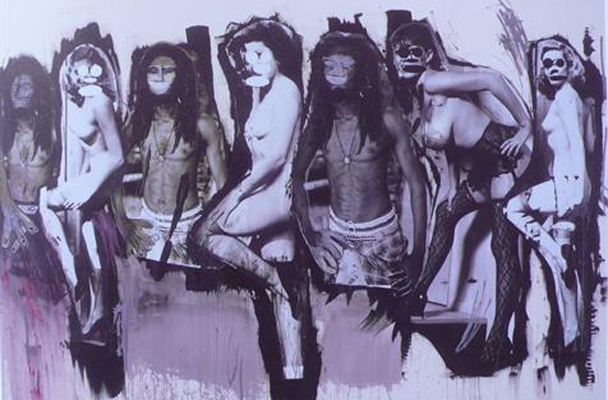

Image: Richard Prince mash-up of photographs by Patrick Cariou: Photo: Patrick Cariou blogspot

The Australian Law Reform Commissions Review (ALRC) into Copyright and the Digital Economy received more than 800 submissions. It was presented to the Attorney General in November 2013 with the recommendation that Australia introduce fair use provisions to the Copyright Act similar to those of the United States.

A fair use system would remove the need to gain specific permission to use an artist’s work without permission provided the user can show the use was ‘fair’. What is fair would need to be based in community expectations and previous practice through common law but would not be defined in law.

The recommendation has received a mixed reception from the arts sector, as was clear from the recent VIVIID : IDEAS panel discussion. If the assembled professionals were a reflection of the broader views held within the sector, then they are both passionately vocal and rigidly polarised.

At one end of the specrum, the Art Law Centre of Australia calls fair use ‘an erosion of artist’s rights’. At the other, the ARC Centre for Excellence and Creative Industries and Innovation says that ‘it is essential for the lifeblood of democracy, commerce and the development of new knowledge’.

The key question underlying the conflict is how we navigate use within a world of ever-expanding access and circulation via technology. Can “change” be adequately dealt with through existing fair dealing exceptions and new legislation, which is a lengthy parliamentary process, or does the technology demand a fair use of copyright material be recognised?

Trish Hepworth, Executive Officer of Australian Digital Alliance, which represents the interests of schools, libraries, museums consumers, tech companies – the people who use and curate but do not make – emphasised the need for a new copyright system to deal with the wide variety of potential uses available to digital users.

An advocate of fair use, Hepworth said that while she loved copyright, our current system was flawed. ‘If you want to use anything it is like threading a rope through the eye of the needle. Sometimes you can’t find the person to ask permission…anything that doesn’t fit in pre-defined exceptions, such as “orphaned books”, fall outside the scope (of our current Copyright Act). All those emails and blog posts, the grey literature, the doodles communicated on the internet are treated in exactly same way as highly artistic, highly valuable, highly commercialised works, and that leads to problems.’

The ALRC case for fair use in Australia argues that it is focused around the nature of the use. ‘Fair use asks four fundamental questions: what are you doing, what are you using, how much of it and what harm is that going to have on the Copyright laws of market?’

But opponents of fair use object to the loss of control for copyright-holders. ‘Fair use is a winner takes all model’ and it does little in advancing the right’s owners position,’ said Zoë Rodriguez, a Copyright lawyer with Copyright Agency, who specialises in author relations and manages the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund.

Vanessa Hutley General Manager of Music Rights Australia said fair use is much more complicated than the reform agenda suggests: ‘The word simplicity is used all the time, as if fair use is going to create greater clarity. This clarity is going to be years in the making and many hours of litigation.’ Huntely voiced a concern shared by many in how the introduction of fair use will play out in terms of the moral rights section in the Act.

But Hepworth argued there should be a differentiation between legal and moral rights. ‘Legally speaking, copyright is an economic property right, and then you have this separate moral rights, which is the right of integrity to your work and the right of attribution. What do I use to judge whether I have the ability to use something without asking permission? I look whether it is for clear public purpose, a good public purpose. I look at how much I am taking and what I am doing with that work, and I look at that harm to market.’

Brendan Coady, a Partner at Maddocks agreed: ‘It is important to recognise that Copyright…has always had particular bounds and scopes and runs for a particular period. It is not, and has never been, unlimited protection and it is subject to exceptions.’ He added, ‘There is a balance that needs to be struck by legislation setting public policy and the people who need to use that material. It is not always practical to get the permission.’

For artists, the case of Cariou v. Prince (March 2014) is key to the problem. Photographer Patrick Cariou lived for six years in a Rastafarian community and produced a series of anthropological photographs to which he held copyright. Artist Richard Price “remixed” the images to create new art works, which he sold for profit.

Left, a photo of a Rastafarian from Patrick Cariou’s “Yes, Rasta” series and, right, a painting from Prince’s “Canal Zone” series “Graduation”; © Richard Prince. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery. Photography by Robert McKeever.

Prince won the case as the work deemed was “transformative”, setting new boundaries for fair use. Remembering that ALRC has recommended that we follow a similar fair use path, this is what VIVD’s panel of lawyers had to say.

Rodriguez believed the case was problematic as it is asked the court to make a decision based on artistic aesthetics. She repeated the words of the judge: “I am not qualified to do this; I should not be asked to do this.”

‘I question whether that is the fair use we want? It underlines the problem that it doesn’t create certainly.’ Rodriguez further cited the Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music case where a rap group created a play on Roy Orbison’s Pretty Woman, the court stating that a commercial parody can qualify as fair use. That money is made does not make it impossible for a use to be fair, quoting the judgment’s definition, she added: ‘fair use is a content specific case by case analysis.’

‘The Australian Copyright system creates relative certainty and is based on the fundamental principle of respect – “ask before you take”’ implying the question why go down this other path?

Nicolas Suzor, Senior Lecturer at Queensland University of Technology School of Law in the areas of copyright, cyberlaw, constitutional law, and jurisprudence, plus researcher at the interdisciplinary ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation, pointed out that the Cariou case did not harm the photographer’s licenses, royalties or income. ‘The harm that was caused was because we think it is unfair to copy.’

‘The point that Picasso, Stravinsky, Steve Jobs and Banksy have all made is – good artists copy but great steal. Creativity is fundamentally remixing transforming existing expressions,’ he added.

Rodriguez interjected: ‘I like my neighbour’s Jaguar but I can’t take it!’

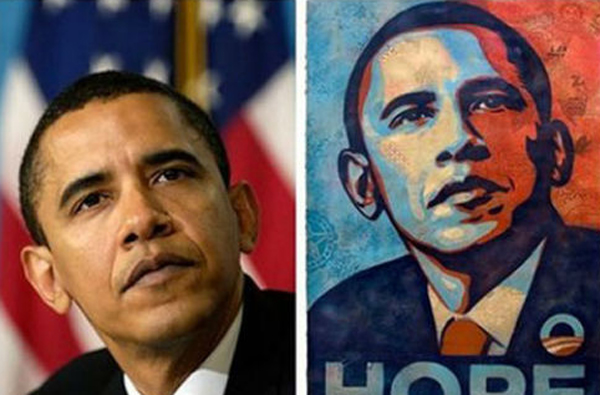

Suzor went on to cite Van Gogh’s letters to his brother where he explained how critical it was to copy the people who inspired him as part of his creative process. ‘He is learning through imitating, but he is also transforming and creating new expression and, fundamentally, I don’t thing this is very different from what Prince is doing, or what Shepard Fairey is doing here with image of Barak Obama using ACP photographer Mannie Garcia, or what Men at Work did when they used two bars of (Marion Sinclair’s) Kookaburra sits on old gum tree. No one accidently buys the wrong record. It just doesn’t compete in the market.’

Fairey’s “Hope” poster for the 2008 Obama presidential campaign. In response to claims by the Associated Press for compensation, Fairey sued for a declaratory judgment that his poster was a fair use of the original photograph. The parties settled out of court in January 2011.

Rodriguez pushed her point: ‘At the end of the day our Copyright Act says that the creator is the owner of Copyright in their works. It is their choice to give it away.’

Coady joined in: ‘It is important to remember that Copyright is a statutory creation. It is not a God-given right, and it is something legislators have put in place to create a balance. I am not advocating inserting just a one-line fair use thing and leave it to the judges to go for their lives.’

‘I spend my life doing advising clients what does this clause mean and we make a best guess on how the courts might interpret that. The more complex the law is the more difficult and uncertain it is. Even the judges are in some cases are unable to interpret – you will see one decision in the Federal Court then overturned in the Full Court,’ added Coady.

Coady pointed out difficulty in getting clear direction from cases under the current law such as in the recent case of Optus TV. Optus obviously engaged a lot of highly paid copyright lawyers to help them design a system that would enable people to record television to view on their mobile devices, which they thought fell within the existing exception 111.’ The rights holders took them to the Federal Court, which Optus won, but then the full court overturned that decision and the High Court refused legal appeal. It had ‘nothing to do with whether it was fair or acceptable behavior. It turned on a very technical question. Even though it was the user decision whether or not to record, they ruled that in fact it was Optus who participates in making the recording and it not for Optus’s personal use.’

The ruling did little to advance the debate and the clarity of our current system, to explain how the exception should function or how a different technological solution might have met the exception.

Coady added, ‘I feel that the fair use exemption is definitely the direction we should be moving rather than tweaking very detailed focused exemptions’, creating an ever-more complex minefield of legislation to navigate.

Suzor described the case of Google Books as another problematic example. ‘Google wants to digitise the world’s books and this is very difficult to do without something like fair use. As an incentive to expend a lot of money to do something which, ultimately, is a public good, Google is going to run ads on top of the books, but there is a commercial element there and the authors are worried about that element.’

Rodriguez, whose parents are both writers whom Google has lifted without permission, said this case illustrates the problems of fair use. ‘There are a lot of authors that say, “Why should Google copy 100% of my work”. Yeah it comes up in snippets in their search terms, but they make a lot of money out of it, and why should they be able to do that with out any return to rights owners? It is up to rights’ owners whether they want to exploit their work in that way – not Google.’

Coady – while stating he didn’t have a firm view on the case – made the point that, ‘many of the works when they were created, Google Books was just not in contemplation, and it is very hard to apply to a set circumstances that couldn’t have been conceived of (and the kinds of markets exposed to).’

So where does that leave us moving forward?

How have these case studies help create a landscape within which fair use can exist in Australia? Are we just creating a “lawyer’s picnic” or would it free up the future?

Rodriguez concluded by making the point that, ‘the online environment was covered when the act changed in 2000. The basic concepts stay the same, it just is online.’ Advocating that our Copyright system was not in peril.

Suzor wrapped up his view of where we stand now: ‘The whole act is polarising. I think what we are seeing change, is that people are just getting on with business models that suit both creators and users and that seems to be the way out of the loggerhead at the moment.

‘The current Copyright system doesn’t provide this kind of flexibility, as Zoe (Rodriguez) points out. You have to ask permission before you take and that is a really crucial problem for a lot of normal creative expression.’ He added, ‘I don’t think Creative Commons (CC) goes far enough to making that happen. The worry that unites us is why would be weaken Copyright at a stage when artists are already in such a bad position. That is the wrong way to look at it. I don’t think introducing fair use will make much of a difference – they are not substitutable for artists licenses, royalties – what we are talking about is that, fundamentally, if everything is a remix, then Copyright is a tax on authorship. I worry, in most cases, it is a regressive tax. It is about ordinary acts of creativity that are prevented by that requirement to seek permission in advance.’

Hutley concluded that she was, ‘unconvinced that fair use is going to be the great answer to everything it seems to have suddenly been raised, because last time I looked at America there was a lot of litigation going on.’

She added, ‘If you want Copyright to work it has to work for everyone, and not just for some artists. It’s got to work so that the other sectors that exist, and are also affected by Copyright, can do their daily jobs.’

Coady echoed this need for a “reality reference point”. ‘In the Telecommunications Act there is a concept around what is in the long term interest of end users, and I think in all the Copyright debate it tends to be very much around the short term interests of existing business models and the people are defending them.’

Simply ALRC took the first step, but this issue is far from solved or clear, and as Coady suggests we should be mindful in our industry to keep this dialogue active to avoid the short-sightedness of the current polarisation.

This piece was first published on artshub.com.au in June 2014.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.