Cultural precincts battle for the global marketplace

What is driving the $US250 cultural precinct billion trend? World expert on cultural precincts, Adrian Ellis knows.

‘Cultural precincts appear to be very fashionable right now,’ Adrian Ellis, Director of Global Cultural Districts Network (GCDN), opened his address to the City of Sydney’s Design Excellence 2014 seminar in September with a statement that rings true in many Australian capitals.

Ellis visited Sydney after the recent staging of GCDN’s summit in Dallas with the theme: Re-imagining Cities: Transforming the 21st Century Metropolis, and indeed the launch of City of Sydney’s Creative City masterplan around the same time.

GCDN is a unique federation, based in the US, that offers a platform for those responsible for conceiving, funding, building, and operating cultural districts, to analyse and solve common challenges and provide scope for collaboration.

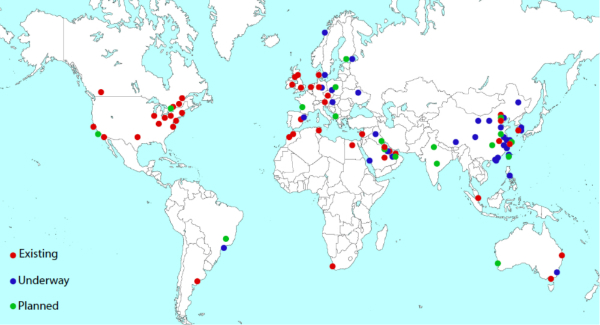

Ellis welcomed Sydney into this global dialogue with a staggering statistic: ‘My company has identified some 75 planned precincts around the world, and over the next decade, some $US250 billion will be invested in the creation of new cultural districts…that is projects that are coming out of the ground now or have a level of government or financial commitment – so assuming they are not froth – that are likely to happen.’

Cultural Districts Around the World; image courtesy SMU Meadows School of the Arts/Masters in International Arts Management

What is going on – what is this convergence of place making and culture on the agenda all about? And, the more obvious question, what is driving it?

Ellis said it is simple. ‘It is globalization. Cities are in competition for assets – competition for global capital, for tourists and cultural tourists, for knowledge workers.’

‘Money spinning around the world faster and faster; ideas and people spinning faster and faster – culture, and the expression of culture, is one of the things that slows it down and decommodifies cities. In other words, cities are using culture as a strategic instrument to assert their identity – their brand – and attract those assets,’ added Elllis.

‘This is about scale – it is not something new,’ said Ellis simply.

Cultural buildings – museums, theaters, performing arts centers, and the like – have played a major role in defining the identity of established global capitals like London, New York, Berlin, and Paris, but many of the entertainment and arts districts in which they are located have developed organically, often over the course of several centuries, and without formal investment strategies.

Today, cultural infrastructure is increasingly planned large-scale and top down: Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi, Beijing’s Olympic Green, Dallas Arts District, Chicago’s Millennium Park, Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District, Singapore’s Esplanade, Doha’s Cultural District offer models of how high-profile urban developments have been planned to embrace cultural activities as an important part of the public realm.

Australia has also embraced the trend, and while Ellis spoke in the context of City of Sydney’s 2030 Creative City masterplan, Melbourne and the Gold Coast and Brisbane have also been vocal this year in announcing their plans.

Regardless of location globally, all these projects are ‘difficult to get right, are expensive and politically embarrassing to get wrong’, said Ellis. ‘They also require a great deal of expertise across a range of disciplines. There is a significant ‘pipeline’ of such projects at the planning and construction stage around the world, in addition to those completed in the past two decades.’

What then constitutes success? And what is the role of the larger cultural institutions as anchors to those cultural precincts?

‘A successful cultural district is not just one that is built, but one that, once built, thrives and, in thriving, animates the city or region that it serves. It is a holistic definition: success is not just getting an arts building or series of buildings out of the ground, it is about ensuring that they are viable and play a central role in their communities.

And to do that, Ellis said the people responsible for the planning of these cultural districts should not from a singular network or power base.

‘Increasingly it is that we (cultural orginsations) are being asked to the table. It is a little strange because at same time, most of them are also involved in a dialogue within the cultural community about the challenges they collectively face for financial stability and changing audiences.’ Ellis added: ‘So at the same time we are a key part of this big idea within the sector we are also being asked to shape up.’

‘This takes us back to beginning – the irony, or paradox, of cultural organisations to the current debate of being successful cities,’ said Ellis. Talk of success urban planning is combined with certain fragility and concern for the long term prospects of those cultural institutions in some places. Such plans place a big bet on these anchor institutions for their overall impact.

‘The point I would make as one plans, moving forward, is that these anchor (organisations) that define a (city’s) identity they are not the whole story. They are the headline of the story; they are in fact the brand.’

‘Their programmatic joie de vivre, if you like, somehow needs to spill out and inform the identity of the precinct. If you come across cultural institutions in survival mode rather than “thrival” mode, you will know. When they are carrying a larger overhead their visions their perspectives are inevitably retrenched.

‘The (bigger picture) cultural strategy requires a real confidence and success in those institutions, and a success that is congruent with the vision of those precincts,’ concluded Ellis.

Ellis made the point that it is vital that there must be synergy between that headline story, ‘between what goes on inside and what goes on outside. There needs to be porosity – a transparency – in which the relationship between is more inter-penetrable.

And in that spirit for Sydney, presenting after Ellis were some of Sydney’s leading cultural institutions, which over the next decade, will be undertaking ambitious capital development programs that will redefine their physical connection to the city.

Dr Michael Brand, Director of Art Gallery of NSW spoke about Sydney Modern; Rose Hiscock, Director of Powerhouse Museum spoke of their recently released five-year vision; Dr Alex Byrne, NSW State Librarian and Chief Executive, State Library NSW spoke of its vision to better locate itself within that perceived cultural ribbon through new galleries and engagement.

Lord Mayor Clover Moore, who made the introductory speech for the night, said: ‘At a time when many of our leading cultural institutions are planning ambitious new developments it is important to look at the relationship and connectivity between our cultural buildings and precious public spaces. 2030 had that very big conversation with Sydney.’

Bruce Baird AM, Chairman, Tourism and Transport Forum and Board Member, Sydney Theatre Company, Elizabeth Ann Macgregor OBE, Director, Museum of Contemporary Art, Malcolm Snow, Chief Executive, National Capital Authority and Professor Peter Tregear, Head of the School of Music, Australian National University joined in panel discussion chaired by Fenella Kernebone.

GCDN is an initiative of the New Cities Foundation, Dallas Arts District, and AEA Consulting.

You can also watch a podcast of the seminar via the City of Sydney website.

This article was first published on ArtsHub.com.au in September 2014.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.